In 1974, Francis Ford Coppola made a movie about surveillance called The Conversation in which Gene Hackman plays a surveillance expert named Harry Caul.

Surveillance is the art not just of listening, but of pinpointing which sounds, which signals, which frequencies are the important ones.

[This article is also available as a video on YouTube.]

To Harry, this is only a job, and just as he absolves himself from caring about what his targets, Mark and Ann, are saying or why his client wants to record them, the soundtrack shifts into discordant music—chords that are severely out of tune—in an oddly beautiful theme song composed for the movie by David Shire.

In an unwelcome irony for Harry Caul, his landlady has been reading his mail and letting herself into his apartment, introducing a theme in the movie best articulated by Hamlet’s Ophelia:“The observed of all observers, quite, quite down!” On this particular day, Harry’s landlady unlocks his apartment door to leave him a bottle of champagne for his birthday. And it turns out there’s a discrepancy regarding Harry’s age; the landlady guesses 44, and Harry tells his friend he’s turning 42.

But for someone in the business of gathering and pinpointing sound frequency, and considering the fact that Harry’s also a musician, both numbers are significant. In the harmonic series, they express the musical notes of F and F#, two notes that show up in both Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut and Shakespeare’s King Lear, and which highlight the devil in music: the tritone. It’s a tone that’s jarring to the ear when played against the harmonic fundamental note of C, and it’s also the note that’s displaced the perfect 5th, G, at the center or mese of the diatonic scale. For more information on that, please read Chapter 14 of The Next Octave.

In his blog, Austin Ross writes that the dissonant soundtrack of The Conversation is full of tritones, and as we’ll see, frequencies aren’t always meant to entertain. Surveillance frequencies, for example, perform a different series of tasks, as do mining frequencies, and the intervals between these working frequencies have nothing to do with pleasing the ear.

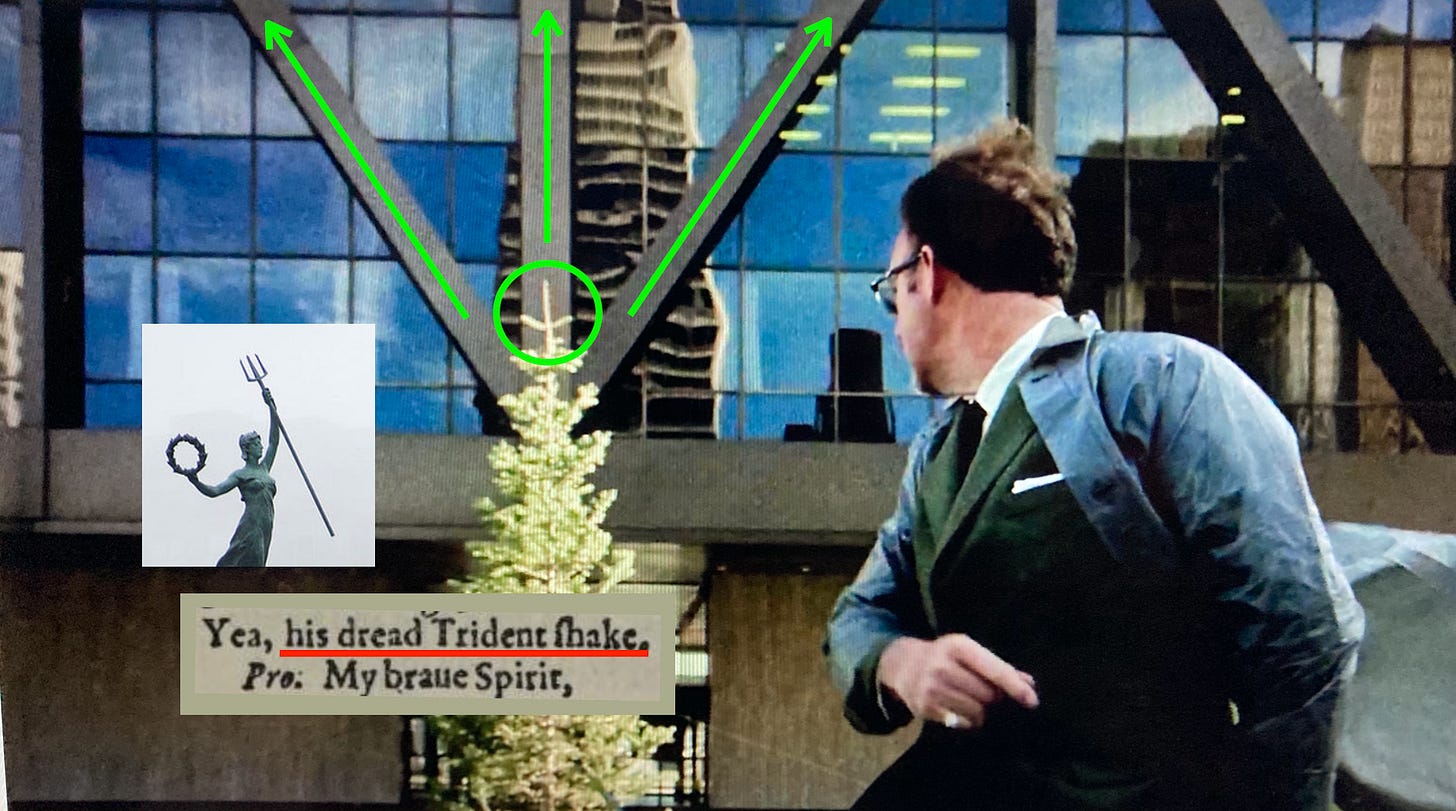

There’s some very obvious symbolism in the movie, as well, but only to those with eyes to see. When Caul delivers his recording, he approaches this sculpture outside Embarcadero Center, called Two Columns with Wedge by Willi Gutmann. From this perspective, the sculpture looks like a giant pipe from a pipe organ, or maybe a dog whistle, too high in frequency for humans to hear.

As Harry finally isolates Mark’s jumbled, initially inaudible comment, “He’d kill us if he got the chance,” he looks at a photo of Ann with the words “Spanish Fleet” above her head. The words are from an inscription on the park’s Dewey monument, the large column in the center of Union Square park that amazingly survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake intact. The monument commemorates the US victory in the Spanish-American war, and according to the State department’s website, “The Spanish-American War of 1898 ended Spain's colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere and secured the position of the United States as a Pacific power.” Spain’s influence will become relevant later in the video.

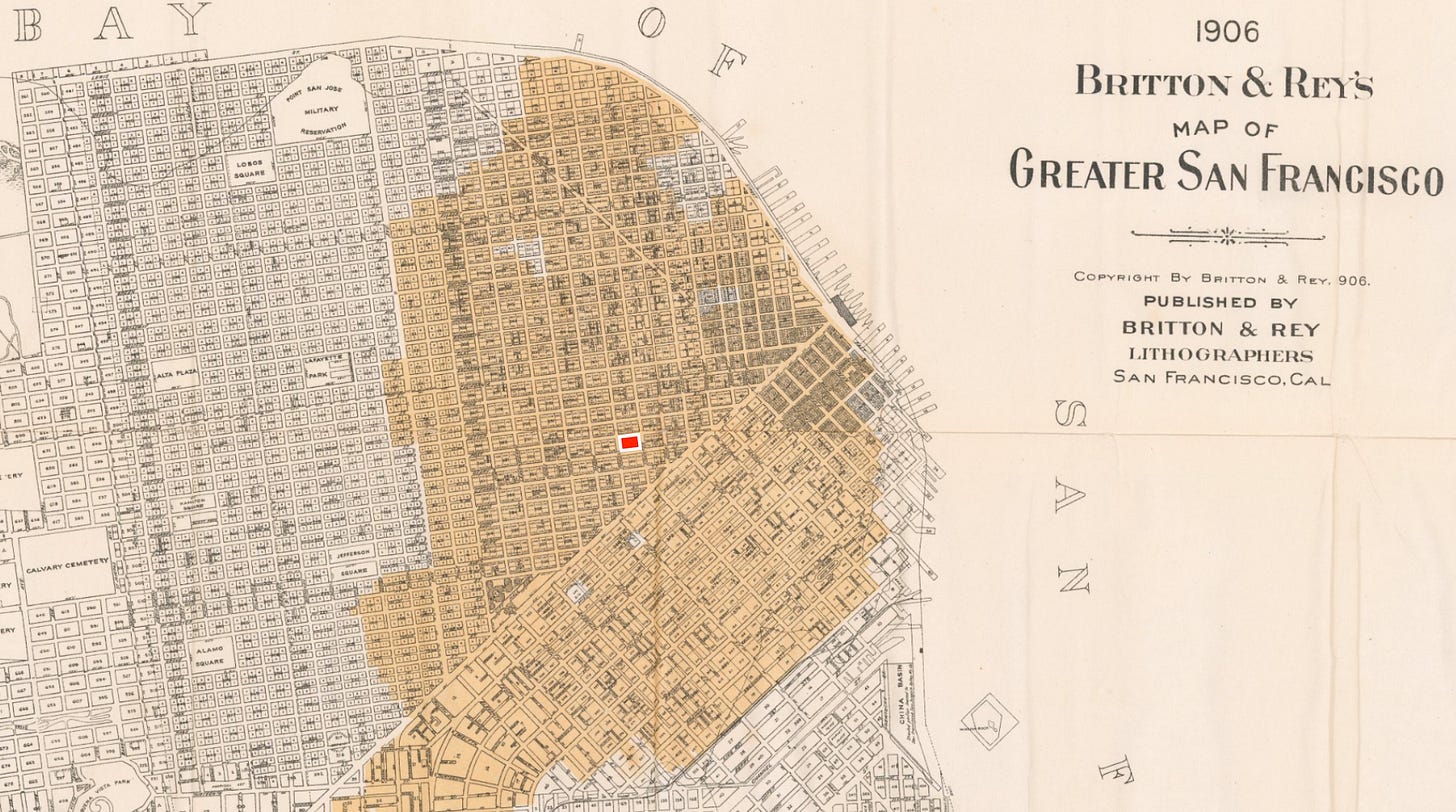

The Dewey monument today is very different from the first one, erected in 1903. The original, shown here having survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, was much shorter, with only six sections of its column shaft, compared with nine today. To survive the intense shaking of the 7.9 magnitude quake, the monument must have used a fairly deep ground anchor penetrating into the earth. And it’s interesting to see that the intact monument ended up at the center or mese of the burn area map after the quake.

A mantle or stone ridge overhung the inscription on the original base, a feature that’s gone today. What hasn’t changed, though, is the fact that Winged Victory on the very top of the Dewey monument, still holds a trident.

Allusions to the plays of Shakespeare are peppered throughout The Conversation. Harry Caul’s last name could refer to Prince Hamlet, himself, who was born a “caulbearer,” something his mother, Queen Gertrude, alludes to when describing his veiled eyelids. A caul is the amniotic sac still clinging to an infant’s head and body, looking like a veil and described as a shimmery coating or garment. Because of this, in Elizabethan times, such children were thought to occupy both sides of the proverbial veil and to be privy to secrets of the dead. It’s because of his caul at birth that Hamlet was thought to have a strong connection to the ghost of his dead father.

A well-known act of surveillance is carried out in the play Hamlet; it’s done by Polonius hiding behind a veil. Polonius tells King Claudius that, “behind the arras I’ll convey myself to hear the process… tis meet that some more audience than a mother… should overhear the speech of vantage.” He’s hiding behind an arras, a tapestry that conceals an alcove. This act of surveillance gets Polonius killed, when Hamlet suspects an intruder and stabs Polonius through the arras. The word surveillance includes the root word “veil,” which originally meant vellum in Latin. The prefix sur- can mean either above or beyond, which suggests that surveillance is the act of moving beyond the veil, though many prepositions would seem to work, including behind or even through the veil.

The fact that Claudius poisoned Hamlet’s father in his ear suggests something inherently dangerous involved in the act of listening.

The Conversation is a movie about the “observed of all observers,” not to mention the hypocrisy of a surveillance expert insisting on his own privacy. It’s about the juxtaposition of transparent raincoats with two-sided mirrors. It’s about an invisible man, a modern-day Prospero, from Shakespeare’s Tempest, transmuting the pine tree into an Ariel antenna at which Neptune, himself, would shake his trident.

Down under

Many people think the Pine Gap military facility in the center of Australia, was named for the cloven pine in The Tempest, the tree that imprisoned Ariel until the magician Prospero “gaped” the tree and freed the spirit.

Some also think the town of Alice Springs, near Pine Gap, was named for the character in Alice in Wonderland, a girl whose mind goes straight to Australia as she tumbles down a rabbit hole in a “down-under” underground experience: “I wonder if I shall fall right through the earth! How funny it’ll seem to come out among the people that walk with their heads downward! …but I shall have to ask them what the name of the country is, you know. Please, Ma’am, is this New Zealand or Australia?”

The mainstream narrative, though, would disagree on both counts. The namesake of Alice Springs is given as a woman named Alice Todd, the wife of Sir Charles Todd who built a telegraph station here in the early 1870s.

And Pine Gap was named for its proximity to Heavitree Gap, just a few miles away, and which isn’t a gap in a tree, but in a ridge of earth. That’s the explanation, but we might wonder how Heavitree Gap got its name? A large, heavy tree, toppled over, is exactly how this landscape appears from above. Various gaps in this lower ridge cause it to appear offset, almost as if its pieces are giant, broken logs that have fallen over.

Eavesdropping

Australia’s Pine Gap is all about sound. As a surveillance facility, Pine Gap listens to sounds.

Despite the presence of Alice Todd, young Alice is still relevant to our story and her time in Wonderland was also punctuated by sounds: teacups rattling, the pig-baby sneezing, dishes crashing, a Gryphon shrieking, a slate-pencil squeaking… but in Wonderland, nobody else seemed to actually be listening, at least to Alice. In fact, except for the Queen listening, a hat-tip to government surveillance, it’s mainly Alice who is hearing things. While her listeners in the story are few, she’s hearing noises upwards of 50 times, while wondering if anybody is hearing her.

Like Wonderland, the island in The Tempest is also full of sounds. The first line of the play is a stage direction, “A tempestuous noise,” linking the storm to the sound it makes and the setting is described early on by Caliban as an isle “full of noises”: watch-dogs barking, roosters crowing, Ariel moaning, a thousand twangling instruments, and sea nymphs ringing a ding-dong bell.

Some of the worst noises on Prospero’s island were created by the witch, Caliban’s mother: “This damn’d Witch, Sycorax For mischiefes manifold, and sorceries terrible To enter humane hearing…” She had imprisoned Ariel for refusing to do her bidding, and as Prospero reminds him, “thy groans Did make wolves howl and penetrate the breasts Of ever angry bears: it was a torment To lay upon the damn’d.”

Prospero commits several acts of surveillance in The Tempest, a task he describes at one point as, “observation strange.” When he’s present during the conversations of others, his magical charms give him the power of invisibility. In his own words, “My high charms work, And these mine enemies are all knit up In their distractions: they now are in my power…” which is always the reason to perform surveillance: to gain power over one’s enemies… something to keep in mind considering Pine Gap’s habit of surveilling the phone conversations of US, British, and Australian citizens.

In addition to the name Pine Gap, the surveillance base near Alice Springs also has a codename: Operation RAINFALL, a weather event precipitating the need for eaves, and from which comes, coincidentally, the term “eavesdrop.” One detail to note from The Conversation is that Harry Caul wears a raincoat all through the movie, even on sunny days.

Rainfall in the Australian outback can be unpredictable, causing both floods and drought. Obviously, the desert areas of the Australian bush suffer extreme drought during certain periods of the year. And it’s likely that Pine Gap is patched into the weather modification apparatus of HAARP, but that’s no secret. The admission below is from an Australian government website.

Droughts and flooding, though, aren’t the only problems here: the soil conditions in this desert climate are also highly saline, meaning they have a high salt content. When Edward John Eyre, the man for whom the Eyre Highway is named, first explored the outback in 1840, he documented this and made an odd comment in his journal: “[T]he very saline nature of the soil in the surrounding country made even the rain water salt, after lying for an hour or two upon the ground.”

Obviously, rainfall, itself, doesn’t contain much salt, but this description of Australia reflects oddly similar imagery involving salt water in Hamlet, The Tempest, and Alice in Wonderland.

Prospero’s island in Shakespeare’s Tempest is also salty, and Caliban alludes to that when he’s insulting Trinculo: “He shall drink nought but brine; for I'll not show him Where the quick freshes are.” Caliban also refers to the island’s brine pits.

In Hamlet, we actually see imagery of salt rain in the reactions of Laertes and Ophelia to their father’s death, their father being Polonius, the one eavesdropping behind the arras veil:

“…tears seven times salt, Burn out the sense and virtue of mine eye.”

and “…on his grave rains many a tear.”

We see something very similar in The Tempest, when Ariel tells Prospero what’s happening with the sailors: “the good old Lord Gonzalo, His Teares runs downe his beard like winters drops from eaves of reeds…” (emphasis added)

Salt water raining into an Elsinore grave and Caliban’s brine pits form a collection of related imagery, similar to one of Australia’s brine pits that Eyre records in his journal: “Following the arm downwards I came to a long reach of water in its channel, about two feet deep, perfectly clear, and as salt as the sea, and I even fancied that it had that peculiar green tinge which sea-water when shallow usually exhibits.” Eyre’s description is brought to life by Antonio and Sebastian in The Tempest: “The ground, indeed, is tawny.” “With an eye of green in’t.”

Brine pit imagery appears in Alice in Wonderland’s pool of tears, where Alice—still underground, literally trapped within the soil—has cried gallons of tears: “… she was up to her chin in salt water… she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.” Her experience echoes the myth of Pirene, the sea nymph, who cried so much over the loss of her son, Cenchrias, that she transmuted herself into the Pirene spring of Corinth.

Coming full circle we find that Pirene means “of the osiers” or the willow, the weeping tree that grew “aslant” over the brook into which Hamlet’s Ophelia fell and drowned, pulled down by her wet garments. Alice worries that she’ll drown in her own tears, and spends an entire chapter attempting to dry her clothes.

But it’s in The Tempest that the most remarkable thing happens to clothes immersed in brine water, as the sailors are amazed to find that, “our garments, being, as they were, drenched in the sea, hold, notwithstanding, their freshness and glosses, being rather new-dyed than stained with salt water.”

Water, salt, and wet garments—whether covered by raincoats or not—seem to be a theme connecting a movie, these three stories, and Pine Gap as Operation RAINFALL, but stranger still, this theme may be relevant to Pine Gap’s other codename connected to clothes: Operation MERINO.

The Golden Fleece

History tells us that Merino sheep were first bred in Spain in the 1200s because of their ability to produce “fine wool,” for garments, as opposed to coarse wool for rugs, and this is one potential reason that The Tempest, Hamlet, and Alice in Wonderland were so focused on garments soaked in salt water.

One area known for its Merino population is the Pyrenees Mountain region of northern Spain, that bleeds up into southern France. Merinos were so prized by the Spanish that they held a strict monopoly over the breed, and unauthorized possession was punishable by death. Eventually, though, Merino sheep began showing up in places other than Spain. Hernán Cortés brought Spanish sheep, including Merinos, to several missions in Mexico in 1538. We might say the Spanish fleet brought over the Spanish fleece that eventually populated the southwestern United States. According to this history on sheep in the American southwest, “Half a century later, in 1598, Juan de Onate who was originally from the Pyrennes (sic) Mountains in Spain, brought with him large flocks of Navajo-Churro and Merinos to the Rio Grande Valley.”

Merinos had also showed up in Australia by the late 1700s. They’ve been very well suited to the dry, saline condition of the soil in both the southwest U.S. and the Australian outback and there are several Merino herds just south of Alice Springs and Pine Gap at Rawlinna Station. It’s the link between Merinos and the Golden Fleece that may explain why Pine Gap uses MERINO as another of its codenames.

“In a 1973 paper published in Nature,” writes Dr. Karl Shuker, “doctors Ryder and Hedges from the Animal Breeding Research Organisation at Edinburgh, Scotland, suggested that the legend of the Golden Fleece may actually refer to fine wool,” the same kind produced by Merinos. But if Merinos weren’t bred for fine wool by the Spanish until the 13th century AD, how do we explain the legend of a golden fleece of fine wool from real sheep circulating in 1300 BC?

The answer, as many of our mysteries do, involves the Tartarians, or rather the Scythians living west of greater Tartary. According to Peter Heylyn’s Microcosmos, published in 1633, this area called Tartaria was originally known as Scythia, and the Scythians eventually became the Huns, Franks, Bulgarians, Tartarians, Visigoths, and several others.

In their 1973 paper, Ryder and Hedges point to a fragment of fine-wool cloth found in a Scythian tomb in Crimea dating to the 5th Century BC. The Crimean penninsula, where this Scythian or Tartarian wool was found, sits at the north end of the Black Sea. And Colchis, where the Greek legend places the Golden Fleece, is just over on the Black Sea’s eastern shore, only 500 miles away.

And oddly enough, the Crimean penninsula sits directly on the sylvanite triangle that I’ve discussed in earlier videos—a triangle that connects the four major sylvanite locations of Kalgoorlie, Transylvania, Romania, Kirkland Lakes, Ontario and Cripple Creek, Colorado.

As the history of many groups living in the area of Tartary has been scrubbed, this could be why we’re having to rediscover this link now. Dr. Karl Shuker states on his blog that, “Its age and Crimean locality collectively confirm that fine wool was indeed associated with the Black Sea region, and at a time near that of the Golden Fleece's appearance and Jason's quest for it.”

In the story of Jason and the Argonauts, the group on a quest for the Golden Fleece, Jason is identified as the hero when he loses one of his sandals in the river Anauros. The meaning of the river’s name is explained on Wiktionary as “waterless,” at which point the webstie blathers on about the prefix “an-“ being attached to an “unknown word for water.” My guess, considering its context, is that the unknown root word of -aurus is related to the Latin word aurum, meaning gold, and from which we get the AU designation for gold in the Periodic Table. Likely the Anaurus was a river with alluvial gold, which is gold deposited by the movement of water. And gold tends to show up in water where there are high salt concentrations, such as in sea water and brine pits.

Jason is assisted on his quest by Hera, the Greek goddess of marriage. He’s also assisted by the sorceress Medea, a female version of Prospero, as both are in the habit of causing people to fall into sleep.

When Jason arrives in Colchis, he’s given tasks to perform before he can take possession of the Golden Fleece. One is to yoke the fire-breathing Colchis Bulls, and plow a field with them. The bulls have hooves of bronze, a reddish colored alloy that will be treading the furrows; this color and connection to the soil is symbolic, as Medea gives Jason an ointment to protect him not only from the fire, but also from iron, the oxide of which turns soils red.

Finally, the golden fleece is hanging from an oak tree, with a dragon coiled around its base. This illustration shows the dragon already slain, but its tail retains its coiled nature. And as this illustration shows, when Jason slays the dragon, it bleeds red into the earth.

The usual explanation given for the presence of gold-colored fleece has been that fleeces are often used to catch particles of alluvial gold flowing downstream in a river. But science is now telling us that the Merinos produce a pigment called lanaurin in their sweat and urine that gives a golden tinge to their wool. Notice that the name given to this pigment, lanaurin, is related to the name of the river Anauros, and both are related to the root word mentioned earlier: aurum, meaning gold.

Merinos are the only breed known to produce lanaurin, and they also happen to be well suited to the desert conditions of the Australian outback, and we find several herds of them just south of Pine Gap and Alice Springs.

The area south of Pine Gap includes the Nullarbor Plain. A few months ago, a youtuber named Rafael Hungria said he’d discovered a star fort in this area, but the feature he found is really more rectangular than star-shaped. And although it’s marked as a “star fort” on Google Maps, the term “Forte Estrela” simply means Star Fort in Portuguese, Hungria’s native language. It’s likely he’s the one who labeled it. There are several similar rectangular dams and brine pits all over this area.

The saline or salty nature of this soil is toxic to most plants, and could explain the lack of trees in the Nullarbor which means, of course, zero trees. But as Eyre explored the area, he wrote in his journal that, “In some parts of the large plains… I had observed traces of the remains of timber, of a larger growth than any now found in the same vicinity, and even in places where none at present exists. Can these plains of such very great extent, and now so open and exposed, have been once clothed with timber? and if so, by what cause, or process, have they been so completely denuded, as not to leave a single tree within a range of many miles?”

Eyre believed there were once trees here, very large trees, so it’s likely the soil didn’t always exhibit these high levels of salt. So what changed?

One factor may have been an increased salinity of the soil due to the introduction of the golden-fleeced Merino. The word “merino” contains the root mer, meaning sea. The suffix -ino means little, so the Merino is being termed a “little sea,” a source of salt water, and the description of the isolated pigment lanaurin, producing its gold fleece, sounds a lot like the black, tarry residue of black alkali, the sodium carbonate residue of certain extremely salty soils.

On the Nullarbor, we find several circular or rectangular dams. Many of these are actually metal water tanks surrounded by paddocks for sheep and several exhibit an area of blackened soil.

According to the Wool Industries Research Association, in their paper published in 1931, the second stage of isolating lanaurin involved an incorporation with ether in solution, which was then evaporated. The result was a “black, tarry residue” with “a most disagreeable smell,” resembling black alkali that’s been described as sticky ooze, or as another article from 1947 states, “vile-smelling, gumbo like muds…”

One of the prime plants on which Merinos feed is saltbush, and it’s one of the few plants that can withstand the presence of black alkali. The conversion of sodium chloride into sodium carbonate, or black alkali, involves ammonia and brine. It’s a patented process called the Solvay process that’s performed in a lime kiln. But what if the urine of Merinos, which of course contains ammonia, is converting the sodium chloride from the saline soil and saltbush into sodium carbonate, and what if this was the natural process used before the Solvey process was patented?

Elsewhere in the Wool Industries Research Association paper, the pigment lanaurin was shown to be precipitated as, again, “a dark and somewhat sticky mass.” And in discussing lanaurin’s solubility, the paper states that it “dissolves readily… in dilute alkali, or sodium carbonate,” which is the defining constituent of black alkali. This might cause us to wonder if excreted lanaurin could be causing this black substance, potentially black alkali, localized around these sheep troughs?

Obviously we can’t know, simply from looking at pictures. Another possibility is that the black areas are concentrations of tar and sulphur to prevent hoof rot in the sheep, spread on the soil so the herd will tread through it.

But the possibility that we might be looking at black alkali indicates a potential for the presence of monatomic elements in the soil. Monatomic elements in the form of a white powder, found in deposits of black alkali, have existed since ancient times, having been found in Egyptian temples, so the possibility not only exists, but seems to be cryptically mentioned by Prospero in The Tempest: “… to tread the ooze Of the salt deep, To run upon the sharp wind of the north, To do me business in the veins o’ the earth When it is baked with frost.”

Here we have the combined imagery of soil, salt, ooze, and a resulting white powder likened to frost. But frost is cold, so what does Prospero mean when he describes the white frost as baked?

Star Fire

Sheep exhibiting golden fleece are in a state of jaundice, a condition of accumulating too much yellow pigment in the bile. In fact, the 1931 Wool Industries Research Association paper states that, “The resemblance between disposition to ‘golden coloration’ in sheep, and… jaundice in man is so marked as to warrant discussion.”

The yellow pigment of jaundice starts out as a reddish-orange pigment because it contains the breakdown of red blood cells, and the pigment’s name is actually red-bile or bilirubin, bili meaning bile and rubin meaning red. The body’s turnover of blood cells requires the processing of old hemoglobin, and the “heme” of hemoglobin is the mineral iron. The Wool Industries report goes on to say that the kidneys of those with hereditary jaundice are rich in iron. We can extrapolate that sheep with golden fleece are experiencing the same effects, including high levels of heme iron in the urine, and this might explain why the soil in areas historically known for the presence of golden-fleeced Merinos have red soil containing high levels of iron oxide. We find these red soils where Merinos have historically grazed, places like the Pyrennes mountains where they were bred, the American southwest where they were brought in the 1500s, and the Australian outback, where Merinos were brought in the 1700s.

The presence of iron oxide in the soil brings to mind Jason’s helper, the goddess Hera, who was described by Homer as “ox-eyed.” The homophone of “oxide” and “ox-eyed” could be dismissed as a cute coincidence, but Hera was the Greek goddess of women, family, and childbirth. As such, she represented blood: the blood of menstruation, childbirth, and kinship. More than a thousand years before Hera was worshipped by the Greeks, the Egyptian goddess Isis represented a deified form of menstrual blood called star fire that was considered both ingestible and medicinal for the gods and rulers.

The Roman church villified the star fire ritual and, though they encouraged the eucharistic drinking of Christ’s blood, the church likened the non-Christian ingestion of blood to vampirism. In light of this, it’s an interesting coincidence that one of the four main locations of sylvanite on earth is in Transylvania.

Because Hera is the goddess of family blood, her Roman counterpart, Juno, is present at the the wedding of Ferdinand and Miranda in The Tempest to bless the union, to bless their bond. This is because the wedding of Ferdinand and Miranda is an alchemical one, the incorporation of iron oxide and saline soil. This is hinted at in their names: Ferdinand is a combination of the medieval term “dinanderie,” a decorative object made from a base metal alloy like bronze or brass, and the prefix fer-, the prefix for ferrum or iron.

Ferdinand and Prospero provide a comic moment in the play, alluding to Ferdinand’s iron through a connection of star fire in the blood and his liver (the liver being the primary storage site of iron in the body:

Prospero: the strongest oaths are straw To the fire i’ the blood…

Ferdinand: I warrant you, sir; The white cold virgin snow upon my heart Abates the ardour of my liver.

Miranda’s name suggests a “mire,” especially when Ferdinand spells it out for us, calling her, “Admir’d.” Miranda then repeatedly describes Ferdinand as noble, but this description is premature; he won’t become noble until he marries his iron with her mire and lays a foundation for transmuted metals, the noble ones like gold, platinum, or palladium, as he tells us—referring to his own task—in Act III: “some kinds of baseness Are nobly undergone.” Likely, it’s Ariel who will help him make a metallic bond, as Ariel describes his attack on the ship as the alchemical processes of chemically separating, heating, and incorporating: “sometime I'ld divide, And burne in many places; on the Top-mast, The Yards and Bore-spritt, would I flame distinctly, Then meete and joyne…” And note that Ariel calls the bowsprit a bore-sprit, not as a pole pertaining to the bow of the ship, but to the act of boring into earth.

In addition to Juno, the Roman counterpart to Hera, we also find the goddess Ceres at the wedding of Ferdinand and Miranda. Ceres is the goddess of fertility, agriculture, and grain. She’s described in the play as bounteous, providing “turfy mountains, where live nibbling sheep, And flat medes thatch’d with stover, them to keep…” The stover left for the sheep to graze is, essentially, dried stalks of harvested grain, and this stover is set against the food conjured during the night by the spirits and elves, who, “By moonshine do the green sour ringlets make, Whereof the ewe not bites…”

This contrasting of sheep fodder is key: it’s pitting acidic food — the unripe grapes conjured by the elves — with alkaline food, the stover, the stalks of harvested grains. One the ewes refuse to bite (the sour, acidic grapes), and one they happily nibble, the alkaline stover, which “keeps them” or sustains them. This isn’t dietary advice for humans; in both cases, the food is referenced as eaten or not eaten by sheep and its relevance has to do with the sheep’s ability to produce golden fleece. The 1931 paper on lanaurin states that golden fleece is related to the pH of the sheep’s urine, which is dependent on diet. Switching to cattle, the researchers noted that most cereal straw (the food provided by bounteous Ceres) produced alkaline urine. Sheep disposed to golden fleece only produced it when eating alkaline straw; when eating acidic food (like unripe grapes) they would not produce golden fleece.

The point is that the grapes must be ripe; they won’t be eaten by ewes the morning after they’re conjured. And, of course, this emphasis on ripe grapes shows up in the play, when Alonso the King notices that, “Trinculo is reeling ripe: where should they Find this grand liquor that hath gilded ’em?” Trinculo has been consuming grapes in the form of wine, but a ripe grape has the alkalinity to gild, to coat something in gold. And King Alonso would know this about gilding because his name means “noble.” He’s older and wiser and more experienced in this than his son Ferdinand, who remains a base alloy of iron that won’t become noble until his chemical wedding later in the play.

The same symbolism shows up in Bacon’s “New Atlantis,” where a cluster of gilded grapes (which means they’re coated with gold) is carried around in public ceremony. This symbol didn’t originate with Bacon, but it’s not surprising that many of these same themes regarding gold and fleece, metal alloys and white powder, even cloven pine, also show up in Bacon’s work.

For example, in Experiment 500 of Sylva Sylvarum, Bacon covers four means proposed to treat a sick tree. The first is to slit the tree root and infuse medicinal substances. He discounts this method “because the Root draweth immediately from the Earth,” meaning any medicine would be diluted by the water and other nutrients the root is drawing. “And besides,” he continues, “it is a long time in going up.” Bacon’s preferred way to treat a tree that’s sick is to “perforate the Body of the Tree,” to cleave the pine, as it were.

We see this image again in Experiment 652, where Bacon describes a cloven or gaped pine and the presence of a white powder: “It is reported, that Firr and Pine, especially if they be old and putrified, though they shine not as some rotten Woods do, yet in the sudden breaking they will sparkle like hard Sugar.” (emphasis added)

Bacon’s broken pine is relevant here, not only to The Tempest and the Pine Gap military facility, but also to a procedure referenced in the 1931 Wool Research paper: the “pine splinter test.” It’s a process involving a cutting of pine to expose fresh wood that’s then treated with hydrochloric acid. When the researchers then placed isolated lanaurin pigment on the treated pine, they obtained a positive, red-colored result, indicating the presence of pyrroles.

A pyrrole is an organic compound found in soil, creosote, and the pigment lanaurin. This paper on its ability to form organometallic complexes with noble metals like ruthenium, osmium, and iridium, states that, “Pyrrole, the five-membered nitrogen heterocycle, is fundamentally integrated into the molecules of life.” Its name comes from the Greek pyrrhos (meaning reddish or fiery) from the reaction used to detect it—the red color that it imparts to wood when moistened with hydrochloric acid.

The Greek king Pyrrhus is mentioned in Hamlet for avenging his own father’s death, and the bard then beats us over the head with imagery pertaining to Hera: “With blood of fathers, mothers, daughters, sons, Baked and impasted with the parching streets, That lend a tyrannous and damned light To their lord's murder: roasted in wrath and fire, And thus o'er-sized with coagulate gore, With eyes like carbuncles, the hellish Pyrrhus…” Much of this imagery relates directly back to Hera and the blood of kinship: fathers, mothers, daughters, sons. But baking and coagulating that blood on the streets also refers to Hera, who was known to have loved three cities for their broad streets. And being “ox-eyed,” of course, is mentioned in the oversized “eyes like carbuncles.”

The red, fiery nature of the pyrroles in lanaurin also shows up in the symbology of the Golden Fleece, as we read in Jason and the Argonauts: “… at that time did Jason uplift the mighty fleece in his hands; and from the shimmering of the flocks of wool there settled on his fair cheeks and brow a red flush like a flame…”

Returning to the Wool Industries Research Association paper, we read that, “It is natural to assume that lanaurin, the pigment of golden coloured wool, is derived ultimately from haemoglobin set free from broken down erythrocytes. The suggestion is supported by the chemical composition of the pigment, and by its undoubted pyrrolic nature.” The red pyrrolic nature of the pigment lanaurin is present not only in the red color of the soils on which Merinos have historically grazed, but also in certain place names including the Spanish Pyrenees mountains. The words Pyrenees and pyrrole both contain the root pyr-, meaning fire. And the morpheme ren, in both Pyrenees and the nearby Rennes-le-Château, suggests renal, pertaining to the kidneys that filter the blood and process urine, while removing salt from the body.

Red soil and its possible connection to the golden-fleeced Merino, the pyrroles and iron oxide of its urine, the Pyrenees of its origin, and the black, gooey alkaline nature of the isolated pigment lanaurin might suggest a connection to the monatomic elements David Hudson found, under similar conditions, on his farm near Pheonix, Arizona, an area to which Merinos were brought from the Pyrenees in 1598. According to Laurence Gardner, the elements Hudson found were in the form of a white powder, reminiscent of snow, that was anciently called both manna and firestone. It functioned as a replacement for the star fire produced by Isis and other female deities.

Monatomic gold (or monatomic platinum, iridium, osmium or any noble metal) is the ultimate end result of an alchemical process, the disincorporation of matter. In Hudson’s patent for the preparation of Orbitally Rearranged Monatomic Gold, we see the central part played by the salt that began our story: “When the salts are dissolved in water and the pH slowly adjusted to neutral, full aquation of the sodium-gold diatom will slowly occur and chloride is removed from the complex. Chemical reduction of the sodium-gold solution results in the formation of a sodium auride. Continued aquation results in disassociation of the gold atom from the sodium and the eventual formation of a protonated auride of gold as a grey precipitate.”

What’s especially interesting about the nature of monatomic elements is their movement from an atomic micro-cluster to a single atom, symbolically represented by the cluster of gilded grapes in “New Atlantis” and the single grape of The Tempest, the “green sour ringlet” not bitten by the sheep. A 1989 article in Scientific American by Duncan and Rouvray framed the idea in terms of Alice in Wonderland: “Divide and subdivide a solid and the traits of its solidity fade away one by one, like the features of the Cheshire Cat, to be replaced by characteristics that are not those of liquids or gases. They belong instead to a new phase of matter, the micro-cluster.”

This might explain why the process of converting salt into black alkali would eventually be patented as the Solvay process, and why Merinos were such a valued breed, apart from their fine wool. If black alkali is the precipitate of monatomic gold, it might very well become a process that adepts would record, but in cipher, occulting its meaning into myth and legend, encoding the process into plays and compendiums to veil its overall significance. And it might be the reason why top secret government surveillance facilities end up in very specific locations.

Australia’s Mese

Pine Gap and Alice Springs are located at the very center of the island of Australia. Pine Gap also falls on the sylvanite triangle. As its line returns from Colorado to Kalgoorlie, it intersects the Pine Gap location at Alice Springs.

Recall that Alice Springs was named for the wife of Sir Charles Todd, who worked under the Astronomer Royal, Sir George Biddell Airy in the 1840s at the Greenwich Observatory. The sylvanite triangle has a strange relationship to Greenwich, as the triangle exactly intersects two prominent points on the International Dateline, which is essentially an extension of the Greenwich Prime Meridian that runs down the opposite side of the world, or so we’re told.

The two prominent points connecting the International Dateline and the sylvanite triangle are: 1) the point at which the Dateline’s deviation to the west, to accommodate Attu of the Aleutian Islands, is corrected, turning back due south, and 2) the point at which the International Dateline crosses the Equator.

The Prime Meridian was placed at Greenwich in London by Sir George Biddell Airy in 1851, though the meridian has since been moved 334 feet further east. A meridian refers to a location on the earth at midday that is directly below the sun, placing it at the midpoint between sunrise and sunset. These are concepts closely related to the mese or the center of a musical scale, the outgrowth of the ancient Greek concept of the meson, or center of a stone, from where we get the term stone “mason.” This is a discovery I first made and published in my book, The Next Octave, in 2021, and, of course, no masons have ever confirmed it.

Geographically, the meson or mese plays a role in earthquake prediction, as explained on the Dutchsinse YouTube channel: when two earthquakes occur, Dutchsinse is usually correct in predicting a third to strike at the centerpoint or mese between them. Just over a month ago, an earthquake as mese showed up in central Australia. Normally, big quakes tend to follow the lines of the plate boundaries, like this one north of Australia. And on January 29, 2024, a 5.1 magnitude earthquake occurred in Papua New Guinea, one of a series of earthquakes along the tectonic plate boundary located here.

But three days later, on February 1, 2024, a smaller 2.0 magnitude earthquake struck down near Perth in Australia. There are no plate boundaries here, and this small quake may have been caused by this intersection of power lines and tower. Dutchsinse sometimes finds power lines emitting extremely low frequencies into the earth to be the cause of quakes. This is not to suggest there’s anything evil about power lines, but we should be aware of the various effects that can occur involving low frequency resonance in the earth.

With these two quakes forming the two endpoints of a line or boundary, we could then predict a third quake to strike at the midpoint between them. And on the following day, on February 2, 2024, a 3.0 earthquake did strike at the midpoint of that line in Tennant Creek. A second 3.1 magnitude quake struck on February 3.

An earthquake at the midpoint between two others is a readjustment for the entire boundary: from one point to the other. And this is also how the harmonic series adjusts as its structural matrix grows. The doubling growth of octaves could easily become cancerous and unmanageable, so each successive octave of growth causes every interval to cleave or divide at the center, the mese, adjusting the octave back into smaller, more manageable intervals so that no interval becomes too large and unsupported by the harmonic structure. We could even say this is a harmonic law: for every doubling, there’s a correspondent halving.

For example, scaling up from the octave of 1 to 2, we’re now in the octave of 2 to 4, but in response to this growth, the harmonic structure demands a division, which is the function of harmonic 3, the mese or perfect 5th of this octave. Now, instead of an octave interval that’s now twice as large as its predecessor, the new, larger interval is “filled” as Plato would say, with the mese, the arithmetic mean.

The octave between 2 and 4 Hz is considered to be in the bottom range of ELFs or extremely low frequencies, shown here in the frequency ranking table. The earthquake predictions that Dutchsinse makes are based on the behavior of a standing wave along a plate boundary exhibiting extremely low frequencies. Earthquakes can be triggered if a force penetrates the earth that resonates with the earth’s low frequency.

Resonance occurs when one object’s vibrational frequency matches the resonant frequency of another, causing the second object to vibrate at the same frequency as the first with no other outside force acting upon it. A good example is when a vibrating tuning fork can cause another fork, tuned to the same resonant frequency, to also vibrate—not because the second fork was ever struck, but simply because it’s in vibrational sympathy with the first fork.

In 1899, Nikola Tesla calculated the natural frequency of the earth to be right around 8 Hz. In 1901, he built Wardenclyffe Tower with a 300-foot ground buried in the earth. According to Wikipedia, “There was a great deal of construction under the tower to establish some form of ground connection but Tesla and his workers kept the public and the press away from the project so little is known. The descriptions… include that the facility had a ten by twelve foot wood and steel lined shaft sunk into the ground 120 feet beneath the tower with a stairway inside it. Tesla stated that at the bottom of the shaft he ‘had special machines rigged up which would push the iron pipe, one length after another, and I pushed these iron pipes, I think sixteen of them, three hundred feet, and then the current through these pipes takes hold of the earth.’ In Tesla's words the function of this was ‘to have a grip on the earth so the whole of this globe can quiver.’” He was using the tower to resonate with the earth’s natural vibrations, and one unintended result was triggering a small earthquake.

In 1953, W.O. Schumann narrowed down the earth’s resonant frequency to 7.83 Hz, a value known as the Schumann Resonance, again, considered to be an extremely low.

Low frequencies tend to slow life down. For example, a 2015 study found that low-frequency sound waves delay the ripening of tomatoes; which may be why people have historically preserved their food underground. The study defined the sound waves used of 1 kHz as “low frequency.” This also suggests that if sound waves can delay the ripening of fruit, like grapes, then sound can be used to alter the acidity found in grapes that are less ripe.

We know that frequency has a palpable effect on matter. High frequency vibrations can clean jewelry, but an article in Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology tells us, “It is generally accepted that a low-frequency vibration has a greater possibility of structural damage than a high-frequency vibration for a certain velocity because the natural frequency of the structures is generally below 10 Hz.” The same is true of the earth’s low resonant frequency of 7.83 Hz; to move the earth, you must speak the earth’s low-frequency language.

Sir George Biddell Airy, the Astronomer Royal and boss of Sir Charles Todd mentioned earlier, also happened to write a book on sound and frequency in 1871. I quoted his book in an earlier video, as I was giving examples of various frequencies used to tune Middle C throughout history. Airy listed several possibilities, but included harmonic C (at 512 Hz) noting its “convenience” due to its ability to be halved, For me and my focus on the mese, this seemed like an important observation on Airy’s part.

But in his book, On Sound and Atmospheric Vibrations, he shares a mystery regarding the direction of frequency. In Article 95, titled, “On cadence, and on some general principles in simple musical composition: with instances of a Ring of Eight Bells, and of the Quarter-Chimes of St. Mary’s Church, Cambridge,” he writes that, “There is a circumstance which we are unable to explain. It would seem possible that, if we rang the bells upwards, from the lowest to the highest, inasmuch as each of the notes has good concord with the highest, we should derive from that series a pleasurable sensation. This, however, does not take place; the effect is unpleasant; and so strongly that (within our knowledge) the ring of the bells in ascending series is used as the alarm-signal of fire or other danger. The difference of effects appears to depend on some unknown physiological cause.” The situation Airy describes calls to mind Ophelia’s instruction to Laertes, “you must sing a-downe, a-downe,” in Hamlet.

Airy sees the jarring effect of ringing bells up as a mystery because “each of the notes has good concord with the highest.” This suggests that it was one of the lower bells of St. Mary’s that may have been the dissonant one. And it does seem to be the lowest bells that are most out of tune.

At 166.5 Hz, Big Ben’s Great Bell, cast in 1856, is considered SLF or “super low frequency.” We’re told it tolls the note of E, though harmonically, 166.5 Hz is a flat F. But even if we just compare the Great Bell with its companion bells, we find that it’s incredibly out of tune with the higher-octave E bell that starts the second of the Westminster Quarters (I give an example of this in the video). This E registers at 340 Hz. Scaling it down to the previous octave, the Great Bell would have to be at 170 Hz for these two bells to be tune, but they’re 3.5 Hz off, making the Great Bell flat enough to perceive with the ear.

Bells

When Paul McCartney performed at the London Olympics in 2012, the giant Olympic Bell hanging onstage started to toll. Sir Paul told NME Magazine that, “During the ceremony, we had a sound glitch… there’s this bloody great bell that we didn't know about. A bloody 50-tonne bell. It was deafening. We were trying to figure out what key it was in, but it was in no key known to mankind.”

The bell was cast especially for the London 2012 Olympics and features the quote from Caliban in The Tempest: “Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises.” There were several other Shakespeare quotes regarding bells that would have worked more poetically, so it’s odd this line was chosen, likening the bell to nothing more than “noise.” And yet, maybe it was appropriate. The bell has been described as “harmonically tuned,” but the fact that one of England’s most celebrated musicians was unable to determine its key suggests that maybe the bell did represent simply a deafening noise.

According to the narrative, the Olympic bell won’t be struck again because it’s too loud, and yet, we assume that because we hear them, these giant bells are meant to be heard. But what if they weren’t always meant to be perceived by human ears? What if the sound waves some of these bells produced were simply meant to vibrate and agitate the ground?

The year 2015 was the hundredth anniversary of the Berkeley Campanile near San Francisco. To celebrate, three Berkeley professors (a composer, roboticist, and artist) translated seismic frequencies from the Hayward Fault line into musical frequencies that the carillon bells rang out in real time. Listening to the performance (in the video), we can hear the dissonance of the seismic “music” and how similar that dissonance is to the David Shire soundtrack of The Conversation.

There’s a borehole array (Integrated Soil Response Arrays) at Embarcadero Four, three buildings down from the sculpture that looks like an organ pipe. Across the street is the Ferry Building with a clock tower that was inspired by the 12th-century Giralda bell tower in Seville, Spain. At the top of each hour, the Ferry Building bells ring the Westminster Quarters, presumably to feed the low, dissonant frequencies down through the borehole array, to start a conversation with the earth in the language of low frequency.

The Berkeley Digital Seismic Network is said to have a data-collection borehole right below the campus bell tower, which calls attention to what is surely a two-way connection, a conversation between the bell frequencies and the ground below. And it’s worth noting that the Berkeley Seismology Lab’s acronym for the Bay Area Regional Deformation Network is BARD.

The imagery calls to mind Ophelia’s singing a-downe, as well as Prospero’s plan to send sound down into the earth: “I’ll break my staff, Bury it certain fathoms in the earth, And deeper than did ever plummet sound I’ll drown my book.” This sending of sound down into the earth is meant to drown his book, sounding very much like a liquefaction event. But that’s a mudflood discussion for another day.

The art of plummeting sound into the ground requires intrusive objects like Prospero’s staff, 16 iron pipes stacked below the Wardenclyffe Tower, or the “bore” sprit of Alonso’s ship. Maybe the Dewey Monument’s very strong ground anchor, capable of withstanding a 7.9 earthquake, being fed mistuned, equally tempered musical frequencies every day by musicians in the park.

Pine Gap’s location on the sylvanite triangle puts it on alignment with Kalgoorlie, one of the four major deposits of sylvanite on earth. Current mining operations in Kalgoorlie involve the Super Pit, with the old Cruickshank Sporting Arena oval situated right next to it. My friend Michelle Gibson has noted the presence of racing tracks in close proximity to airports, in the same linear configuration all over the Earth, and she’s hypothesized that they were part of the Earth's original energy grid system which functioned as a circuit board. These oval tracks show up near mines, as well.

Open-pit mines exist next to all four of the major sylvanite deposits. Chad, of the “Deeper Conversations with Chad” YouTube channel, believes large mines like these to be the dug-out remnants of giant trees, which is entirely plausible, as tree roots, even of normal size, can “pilfer” or transport gold up from the soil, making certain trees useful in locating underground deposits of gold. In an article in National Geographic, researchers state that gold is “taken up by the root system of the trees.”

And when Bacon was warning against applying medicines to tree roots in Experiment 500, due to the fact that, “the Root draweth immediately from the Earth,” I don’t think he was speaking temporally; nor was he referring to the tree drawing water. I believe he was referring to minerals in the immediate vicinity of the root, which is a repetitive though subtle image in Renaissance literature: Aaron burying “so much gold under a tree” in Titus Andronicus or the three cedars in The Chymical Wedding, directing Christian to the location of the wedded tellurides containing both gold and tellurium.

In earlier research, I’ve explained that tellurides like sylvanite are compounds in which the element tellurium binds, or weds, with another like gold or silver. In my video on the telluride of calaverite, I showed tellurium to be the metaphorical sword in the stone of gold, which is why it was so necessary to pull the sword out in the first place: once some king pulls out the sword of tellurium, you’re left with a stone of pure gold.

But tellurium is not to be confused with telluric lines, which are winding, snaking lines of energy that follow the flow of underground streams. According to Guy Underwood, in his 1968 book, The Pattern of the Past, underground streams will often meet, forming a confluence that’s termed a “blind spring.”

Many cathedrals with bell towers were built on top of these springs and confluences, and it’s not unreasonable to think their bells were transferring frequency not only into the earth, but into these springs and the underground currents that connected them. If so, these bells aren’t meant to send vibration through the air, for the benefit of human ears, but through the soil and streams.

In his book, Underwood includes a photo of osiers bending toward a blind spring, which calls to mind the story of Pirene, meaning “of the osiers,” who transmuted herself into the spring in Corinth. It’s also reminiscent of the leaning osier in Hamlet, the willow that “growes aslant a Brooke…” where Ophelia drowns. As the blog Chasing Trees states, “Weeping willow trees seem forever bent in their search for water.”

When a winding telluric line curls into a spiral, it’s called a dragon line. “Beware of the dragons, the great telluric spirals,” a dowser, Colin Bloy, wrote in a 1978 edition of the Journal of Geomancy. “To kill them, impale them on the lance, and fix them in straight lines, channel their sinuosities.” A sinuosity is the ability to curve, and its this curving, twisting nature of fluid dynamics that was central to the life’s work of Viktor Schauberger.

A telluric line spiraling in on itself appears as a serpent eating its own tail, and when the dowser says, impale the spiral on a lance, he’s referring to the act of redirecting telluric energy out of its terminus and back into directional movement somewhere else. People have been manipulating telluric lines for thousands of years, and the process has been woven into legend as the metaphorical slaying of the dragon. The name of the most prominent dragon slayer, St. George, contains the root “geo-” of such words as geology, earth structure, and geometry, earth measurement.

In this engraving of St. George, Albrecht Dürer portrays the turbulent, sinusoidal flow of the dragon’s tail almost identically to an underground stream’s depiction in Underwood’s book.

To procure the Golden Fleece, Jason must also slay a dragon, which brings us full circle, back to the salt water producing “little sea” of the Merino sheep grazing on the red soil of the iron-oxide-Hera. The dowser, Colin Bloy, noted in the Journal of Geomancy that many underground springs terminate “in huge double ram’s horn spirals. We came to call them earth temples.” It’s no coincidence that we locate the spiral horns of rams, in this case a Merino, to be located at the “temples.”

Just like above-ground streams, it’s possible for underground streams to contain alluvial gold, deposited by the movement of water. As above, so below. It’s assumed that it’s the force of moving water that also loosens that gold from rock, but resonant low frequencies could accomplish the same thing. And this could explain why something like a large bell, intended to resonate with the earth’s extremely low frequencies, would sound musically dissonant, vibrating in “no key known to man.”

And in Scotland, we can see how a system involving bell frequencies might’ve been designed and used to loosen alluvial gold. The Ochil Hills area of Scotland is known for its alluvial gold deposits in its streams and burns. Looking at the larger region, we find that extending in both the east and west directions along the Ochil fault line are six ancient churches and cathedrals with bell towers.

The Ochil Hills gold deposits are located in the center or mese of this line of bells, roughly halfway between St. Andrews Cathedral and the Luss Parish Church. What makes this situation even more obvious is that four more bells were added to amplify the low frequencies, in a process that looks very similar to that of triggering quakes in the ground at the mese or midpoint of this set of bells.

The dissonant music in The Conversation, in relation to the topic of surveillance, seems to be a hint that not all frequencies are meant to entertain the ear. And the jarring, mistuned, “jangled” frequencies, especially of bells, are meant to do something else altogether.

Just as governments had to provide the telegraph wire and the cell phone signal before they could eavesdrop on the resulting conversations, governments started a conversation with the earth, herself, and are using her responses against her. And as the dragon spirals and cedar trees have informed on her, giving us a map to the great chymical weddings taking place underground, those in charge have instituted the great chymical divorce, separating the earth from its gold, whether monatomic, alluvial, or in rock.

The one character mentioned many times, but not present in The Tempest, is Alonso’s daughter, Claribell. The play begins as Alonso, the King of Naples, returns home from her wedding to the King of Tunis, and the symbolism is defeaning: Claribell, representing the clarity of a bell, avoids setting foot on Prospero’s “isle full of noises.” Instead, she’s been elevated to the Queen of Tunis, a place name quietly suggesting the concept of being in tune.

What’s more, the location of Tunis occupies the mese of northern Africa. But even though she’s now Queen of Tunis, Claribell retains her position as the “heir of Naples,” a city called Neā́polis in ancient Greek. Funny how similar the root “neā́” is to the ancient Greek word “ennéa,” meaning nine. This makes Antonio’s line full of extra meaning, “how shall… Claribell measure us back to Naples? keepe in Tunis…”

Alice (of Wonderland) was nine feet high when she cried the salt water pool of tears. The Dewey Monument in Union Square park now has nine sections of its column shaft boring into the earth. And nine occupies the mese position of the Mobius Circuit.

I think Francis Bacon was, perhaps, more prescient than we ever realized.

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)

https://t.me/gweverstegen/61943

https://photos.app.goo.gl/6oPFr1427tUY4KBE8