Moriarty, rotary, and foolscap

Just over a year ago, I mentioned in a short teaser video that the name of the Sherlock Holmes character, Professor Moriarty, was an anagram for “I M Rotary.” But did the author, Arthur Conan Doyle, encrypt this anagram on purpose? And if so, what does it mean?

That Doyle included the anagram on purpose is hinted at in the story, “The Final Problem,” when Holmes tells Watson that Moriarty once wrote a treatise on the Binomial Theorem. The term “binomial” suggests the concept of two names. But then the question becomes, whywould Moriarty covertly identify himself as “Rotary”?

Doyle gives some insight on that in his 1915 novel, The Valley of Fear, where Moriarty, and the crime syndicate of which he’s a central figure, are described in rotational terms: “Everything comes in circles—even Professor Moriarty… The old wheel turns, and the same spoke comes up. It’s all been done before, and will be again.” Doyle is drawing up a vicious cycle that repeats indefinitely but this is really just poetic philosophizing. The specific meaning behind I M Rotary goes much deeper than simply the metaphor of a vicious circle.

Moriarty as Rotary represents thieves who use circulation to steal from afar. To understand this provocative idea, we need to do a Moriarty deep-dive, realizing that the overall business of Moriarty’s criminal syndicate was never really thwarted by Holmes or Watson. And Holmes never penetrated this syndicate any further than his confrontation with Moriarty in “The Final Problem.” In fact, Sherlock Holmes existed as an object of mockery with regard to the syndicate’s real business, implemented via the workings of rotary, and that’s because Moriarty’s real crimes targeted every locked home, the SURELY locked home, from which Moriarty and his cartel could steal wealth safely locked up inside.

This was Doyle’s inside joke.

Back then, when Doyle was writing the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, most people didn’t trust banks. Not only did depositors face the risk of thieves, or the bankers, themselves, stealing deposits right out of the vault, but during the last half of the 19th century, bank failures were rampant. Between 1863 and 1913, eight banking panics took place in Manhattan and more than 2000 banks collapsed in the U.S. The public distrusted banks and tended to keep their money at home, under mattresses, buried in holes, or padlocked in strong boxes.

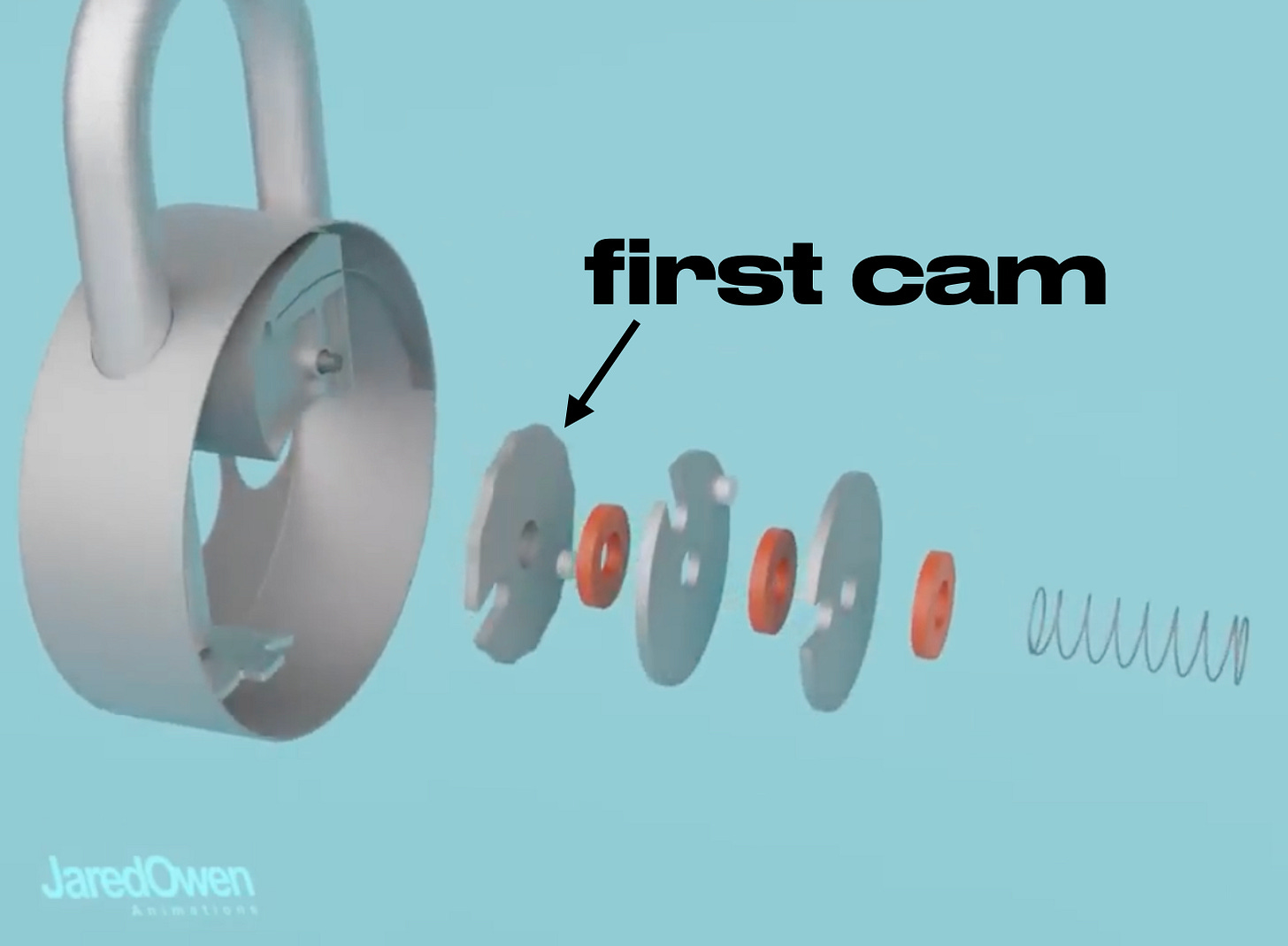

And this brings us to the central, though veiled metaphor of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries: the combination lock, in which a secret code of letters or numbers is used to unlock the mechanism. As YouTuber Jared Owen says in his animation video on such locks, “If the latch can’t rotate, the shackle won’t come out,” meaning that, in order to open a lock, you need rotary movement. Moriarty IS that rotary movement, unlocking the wealth seemingly protected within sure-locked homes.

But there’s another component inside that’s necessary to open a combination lock: something called a cam. Which leads us to another clue in Doyle’s work. According to Holmes, the “worst man in London” is a blackmailer named Charles Augustus Milverton, who identifies himself with his initials, C-A-M. A cam is used to translate rotational movement into linear movement.

In most combination locks, the first cam is attached to the dial, suggesting that a cam can use information to unlock and access treasure.

Charles Augustus Milverton, as a CAM, used secret information purchased from disloyal servants to pry open the locks of the wealthy’s stash of savings. So Moriarty and Milverton are the pickers of locks, even those that are sher-locked. But again, this is all just metaphor. Moriarty and Milverton aren’t actually breaking into padlocked homes to steal wealth. So what is going on here?

The hidden disclosure of Sherlock Holmes is that smart villains don’t need thugs or guns to steal your wealth. They only need de-ciphered information. In modern times, that information might be as simple as your account password. But at the turn of the 19th century, when Arthur Conan Doyle was writing the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, the important information was Moriarty’s knowledge of the rotational mechanism of monetary inflation.

According to Holmes, Moriarty wrote a treatise on the binomial theorem, which is an algebraic formula for the expansion of mathematical “powers” or exponents. Such an understanding lends itself perfectly to the mechanism of monetary inflation, which is explained by the Financial Edge Training website: “Inflation… is usually quite simple to model. In most cases, we simply apply an exponential formula: (1 + rate) ^ number of periods.”

Doyle tells us explicitly that Moriarty and his syndicate possess the knowledge that will rotate open the lock on everybody’s savings strong box, whether held in a bank vault or in a surely locked home. This is because inflation steals the peoples’ purchasing power, a stealth way of stealing from them.

There are two ways to get rich printing money: one is through counterfeiting and the other is by inflating the money supply through the banking system. Counterfeiting is a crime that’s easily understood and Doyle’s characters commit this crime a few times. In “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs,” Watson describes finding a counterfeiter’s printing press belonging to a man named Evans.

But counterfeiting is covered in more detail in Doyle’s novel, The Valley of Fear, the only Sherlock Holmes mystery set in the US. It was published in 1915, just a year and a half after the Federal Reserve, the central bank that controls the country’s money supply, was formed. The first part of the novel is called The Tragedy of Birlstone. The character Porlock, the opposite of Sherlock, uses the name Birlstone in a cryptogram that Holmes must decipher. The word “birl” is a rotationally descriptive term, meaning whirl or spin.

Later in the story we learn that the character named McMurdo is counterfeiting: “I was helping Uncle Sam to make dollars. Maybe mine were not as good gold as his, but they looked as well and were cheaper to make. This man Pinto helped me to shove the queer—”

“’To do what?’

“’Well, it means to pass the dollars out into circulation…’” In order to benefit from printing money, the money must circulate in circular flow. Circulation for a counterfeiter simply means the initial act of spending the fake money, but circulating an increased money supply allows for theft on a much larger scale.

Another mathematician known for his work with the binomial theorem was the real Gerolamo Cardano who lived in the 1500s. According to Wikipedia, “Cardano partially invented and described several mechanical devices, including the combination lock, the gimbal… and the Cardan shaft, which allows the transmission of rotary motion at various angles.” But what stood out to me was his work with hypocycloids, and that’s because these “Cardano circles” were used for the construction of the first high-speed printing presses. The Cardano Circle also resembles the symbol used by the Scowrer’s gang of murderers in The Valley of Fear.

A few years after Cardano died in the Papal States, a German man named John Spilman introduced a specific kind of paper into England called “foolscap.” Its name was based on the paper’s watermark, a jester’s head with his pointed cap and bells.

Arthur Conan Doyle referred to foolscap many times in the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, almost using the term as a stand-in word for paper. One noteable reference was made in “The Adventure of the Red Circle,” when slips of foolscap were presented to Holmes.

“’…If he wants anything else he prints it on a slip of paper and leaves it.’

“’Prints it?’

“’Yes, sir; prints it in pencil. Just the word, nothing more. Here’s the one I brought to show you–soap. Here’s another–match. This is one he left the first morning–Daily Gazette. I leave that paper with his breakfast every morning.’

“’Dear me, Watson,’ said Holmes, staring with great curiosity at the slips of foolscap which the landlady had handed to him, ‘this is certainly a little unusual. Seclusion I can understand; but why print? Printing is a clumsy process. Why not write? What would it suggest, Watson?’”

Doyle uses the word “print” or a variation five times in this short scene. In the story, the word “print” is meant to distinguish the writing from cursive, but printing could also mean the use of a printing press, rotary printing. So why might Doyle want to bring attention to rotary printing on foolscap?

This story, ”The Adventure of the Red Circle,” was printed in 1911, but 50 years earlier, during the Civil War, the Treasury department of the southern Confederate states was purchasing foolscap as its Bank Note paper, following the lead of the U.S. Treasury.

In an article from the website, Society of Paper Money Collectors, we find information about the the department’s purchase of foolscap in 1862: “He stated ‘we make and can buy paper of all kinds as well as any London house; so we could execute your order for foolscap loan paper, with watermark, ‘CSA’… ‘Foolscap’ is a British term meaning a size of drawing or printing paper. However, court records seem to refer to this paper as Bank Note paper, detailing ‘many reams of fine white Bank Note paper, watermarked ‘CSA,’ intended obviously for Confederate States banknotes and bonds.’ It seems from the court records that the United States Treasury Department acquired five cases… The paper bought by the Treasury department was primarily used to print proofs of Fractional Currency.”

Benjamin Franklin wrote a poem comparing different types of paper with certain types of people. For example, mechanics, servants, and farmers were “copy paper,” a virgin maid was “white paper,” and poets were considered “waste paper.” Not surprisingly, Franklin linked foolscap with “retail politicians.” In a similar vein, Doyle was linking foolscap with the money printing of central bankers. Remember that the etymology of the word “cap,” a covering for the head, goes back to the word “capital,” which originally referred to how many “head” of cattle a farmer owned. The term foolscap is telling us, quite literally, that paper money is fool’s capital.

But how exactly does fool’s capital allow Professor Moriarty to steal wealth that’s been sher-ly locked away? That answer is not disclosed by Arthur Conan Doyle, but it is something I show in my book, Inflationary Faeries. In the story, a group of faeries form a central bank in order to complete an initiation task: that of stealing the wealth stored in the basement of Faodail Castle… without using faery magic.

So how is it done? It’s somewhat complex and easier to understand if you read the whole book, but the over-simplified explanation is that a circular flow of inflated money created through debt, debt that’s circulating through an Irish shire, or any economy, will draw savings out from locked vaults in order to service the continually growing debt. An increase in the supply of fool’s capital will increase prices. Once savings has been tapped and shoved back into the economy to pay these higher prices, that savings remains in circulation (circular motion) and the increased size of the economy is now large enough to pay the interest that a debt-based economy continually demands, once that savings circulates into the hands of those in debt.

A few lines after McMurdo explains how counterfeit money is shoved into circulation, McGinty tells him, and really tells us that, “[T]here are times when we have to take our own part. We’d soon be against the wall if we didn’t shove back at those that were pushing us.”

[A video of this post is available here:

]

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)

Rotary is the Flying Dutchman ships 'Steering wheel'... masters of the Wind Trade of AMNION (golden fleece) uterine sacs!