Frankenstein and the Tartarian Strawman

[This article is also available as a video. Thanks to everyone who supports my work. If you would like to contribute, I can always use a cup of coffee! ]

Corporate bodies

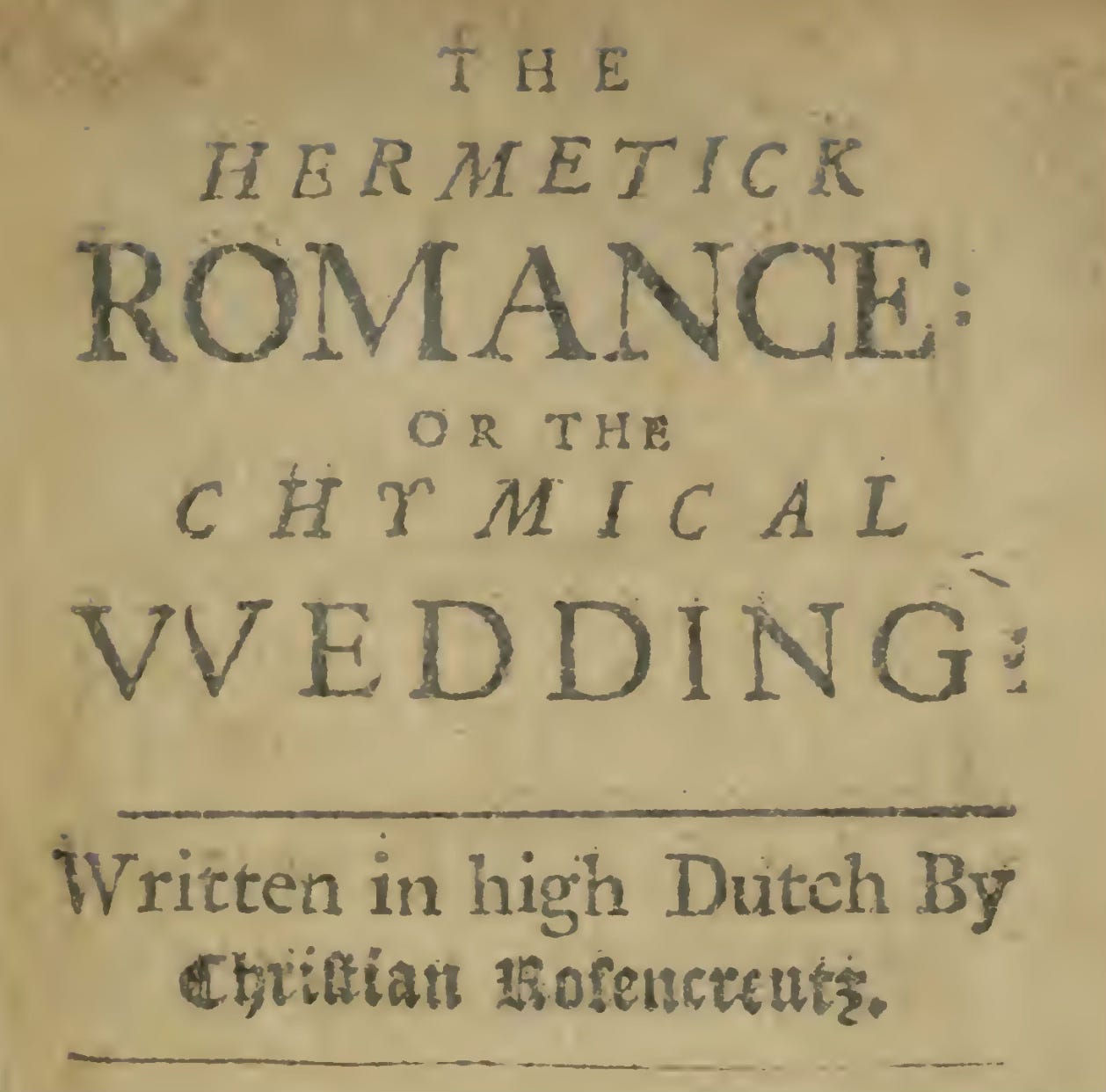

In 1616, a book called The Hermetick Romance or the Chymical Wedding allegorized the act of incorporation as the mysterious bonding between a Royal bride and groom, referred to in the story as the sponsus and sponsa.

Notice that sponsus and sponsa derive from the Latin spondere, meaning “to bind oneself.” The last word is important: it’s not just the act of binding, but of “binding oneself,” pledging or promising yourself. Though rare, the root of “spond” does show up in some Latin-based vocabulary. Ankylosing spondylitis, for example, describes a medical condition in which the spine can fuse.

The root “spond” is a linguistic ancestor of the word “bond,” as the grapheme blend of -sp- has morphed over time into the “b” sound.

sp —> b

spond —> bond

And this is why, in law, the term “respond” can mean to “re-bond yourself.” As such, state nationals and sovereigns often avoid “re-sponding” to government presentments, many of which are legal attempts to re-bind parties of a previous contractual agreement.

On a related note, the Spanish word for bride, esposa, is almost identical to the Spanish word for handcuffs.

A bond binds, and the state of being bound can involve chemical links, legal obligations, handcuffs, and even the state of romance. Sitting conspicuously in the word “romance,” is the root word, Roman, pointing to the Roman Catholic church combining individual souls as pieces of the universal body of the church. In fact, the word “catholic” means universal in the sense of all-encompassing or all-enjoining. From the corporate perspective, individuals—a term originally meaning indivisible—were now seen as simply parts in a greater individual: the church body.

In The Hermetick Romance, a “wedding” of chemical elements, transmutes the sponsus and sponsa into one corporate body, similar to the idea that married couples are defined in Matthew 19:6 as “one flesh.” This bible verse goes on to warn us that, “what therefore God hath joined together, let no man put asunder.” Or, What God has incorporated, let no man separate. This biblical warning points to the fact that the church values incorporation very highly.

Similar in many ways to The Hermetick Romance is Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein. The story’s antagonist, Victor Frankenstein’s monster, is an accurate metaphor depicting the act of chymical incorporation being used to embody, to create a corporate body. The protagonist, Victor Frankenstein himself, represents the counterweight to the corporate body dead entity in the form of a natural, living man. The two play out a dualistic struggle both in the natural world of physical reality and the jurisdictional world of legal fiction.

Mary Shelley doesn’t describe the method of the monster’s embodiment or animation in her novel, but it’s assumed to involve piecing together dead body parts, then sparking the conglomerate body to life with a lightning bolt’s electromagnetic pulse. And lightning works well as a catalyst for the “Hermetic romance,” especially as romantic bonds are often described as the attraction between two lovers experiencing “magnetism” and/or “electricity.”

Another novel, published almost 30 years earlier by François-Félix Nogaret, uses a similar character name: “Vauk-on-son-Frankénsteïn.” And in the 1730s, a real person named Jacques de Vaucanson actually was building automatons or “androids” built of hundreds of metal parts in France; his rusted-gear automatons were hat-tipped in the film The Best Offer with Geoffrey Rush. We don’t know if Shelley read Nogaret’s book, but it is an interesting overlap involving the concept of animating the “conglomerate” or dead corporate entity.

Shelley’s novel opens and closes on shifting blocks of ice in the Arctic Sea. Robert Walton, the story’s narrator, is sailing his hired ship on an expedition to the North Pole. The sailors get stuck in the ice and while they wait for their ship to break free, they spot a giant man driving a dog sled in the same northerly direction. Walton mistakenly assumes the dog sled is traversing on land, and this mistake is key to the story’s subtle act of disclosure:

About two o’clock the mist cleared away, and we beheld, stretched out in every direction, vast and irregular plains of ice, which seemed to have no end. Some of my comrades groaned, and my own mind began to grow watchful with anxious thoughts, when a strange sight suddenly attracted our attention… We perceived a low carriage, fixed on a sledge and drawn by dogs, pass on towards the north, at the distance of half a mile; a being which had the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature, sat in the sledge and guided the dogs. We watched the rapid progress of the traveller with our telescopes until he was lost among the distant inequalities of the ice. This appearance excited our unqualified wonder. We were, as we believed, many hundred miles from any land; but this apparition seemed to denote that it was not, in reality, so distant as we had supposed.

The dog sled is moving on “plains of ice” that form a false land, in stark contradiction to the true land of rock and dirt the dog sled had recently traversed. And the true land’s comparison with the false doesn’t occur until the end of the novel, when we catch back up with this Arctic scene at the story’s beginning:

I continued with unabated fervour to traverse immense deserts, until the ocean appeared at a distance and formed the utmost boundary of the horizon… Covered with ice, it was only to be distinguished from land by its superior wildness and ruggedness… I pressed on, and in two days arrived at a wretched hamlet on the seashore. I inquired of the inhabitants concerning the fiend and gained accurate information. A gigantic monster, they said, had arrived the night before… He had carried off their store of winter food, and placing it in a sledge… had pursued his journey across the sea in a direction that led to no land… I exchanged my land-sledge for one fashioned for the inequalities of the Frozen Ocean, and purchasing a plentiful stock of provisions, I departed from land.

Moving from land to sea is a change in legal jurisdiction, as discussed in my previous video on Admiralty Law. What’s more, this change in jurisdiction from land to sea is being made by a corporate person and a natural man, and that’s central to the novel’s underlying and largely hidden point regarding property rights. That Shelley describes this jurisdiction as full of “inequalities” tells us something about how the author views the jurisdiction of Admiralty.

The Tartarian strawman

As the novel nears its end, the monster has been leading his creator, Victor Frankenstein, on a chase through eastern Europe. Victor is determined to kill his hideous creation and the monster is exacting a hateful revenge of his own, leading Victor into the mysterious region of Tartaria.

Victor gives a brief account of the route of the chase:

Guided by a slight clue, I followed the windings of the Rhone, but vainly. The blue Mediterranean appeared, and by a strange chance, I saw the fiend enter by night and hide himself in a vessel bound for the Black Sea… Amidst the wilds of Tartary and Russia, although he still evaded me, I have ever followed in his track.

Various historical maps place Tartary somewhere between China and Russia. Peter Heylyn stated in his 1633 Microcosmos that Tartaria was originally known as Scythia and Mercator’s 1595 map showed the pink region of Tartaria, including Nagai Tartari and Kasakki Tartari, extending west all the way to the Black Sea.

In 1580, John Frampton deep dived Tartaria for England’s Moscovy Company, an offshoot of the Company of Merchant Adventurers that was formally incorporated in 1555, and was a precursor to the similar British East India Company. The Moscovy Company was originally headquartered in Moscow, but in 1717 the company moved operations to Archangel, a harbor town Walton mentions several times in the novel. In fact, Walton indirectly mentions the company located there in a letter home to his sister: “I shall certainly find no friend on the wide ocean, nor even here in Archangel, among merchants and seamen.”

Such merchant adventurers would sail to various locales looking for trade routes and their travels are pertinent with regard to Shelley’s novel. In fact, Victor Frankenstein and his monster seem to be re-enacting the travels of the merchant adventurers of the mid 1500s looking for a northern trade route to Cathay in northern China.

Frampton’s book for the Moscovy Company offered motivation in the search for this northern trading route, describing the trading potential of Tartaria, Scythia, and Cathay (also known as Cataya) as the reason to continue their search. But in his description of Tartarian customs found on page 10, Frampton noted an odd burial ritual:

…After this the friendes of the deceased, take an other horse, and kill him, and eate his fleshe, and fill the skinne full of hay, and sowing it together, rayse him uppe with foure peeces of timber, uppon the Sepulchre, in token that there is one buried, and the women doe burne the bones, saying that they are for the purgation of the Soule.

The Scythians had a somewhat similar ritual involving the sewing of skin:

There are many of them that sowe the skinnes of men together, as though they were skinnes of beastes…

But why would Frampton bother to report back on such gruesome customs in a study on the region’s trading potential? The answer may lie in the similarity between these rituals and the metaphor of the corporate strawman (“and fill the skinne full of hay”).

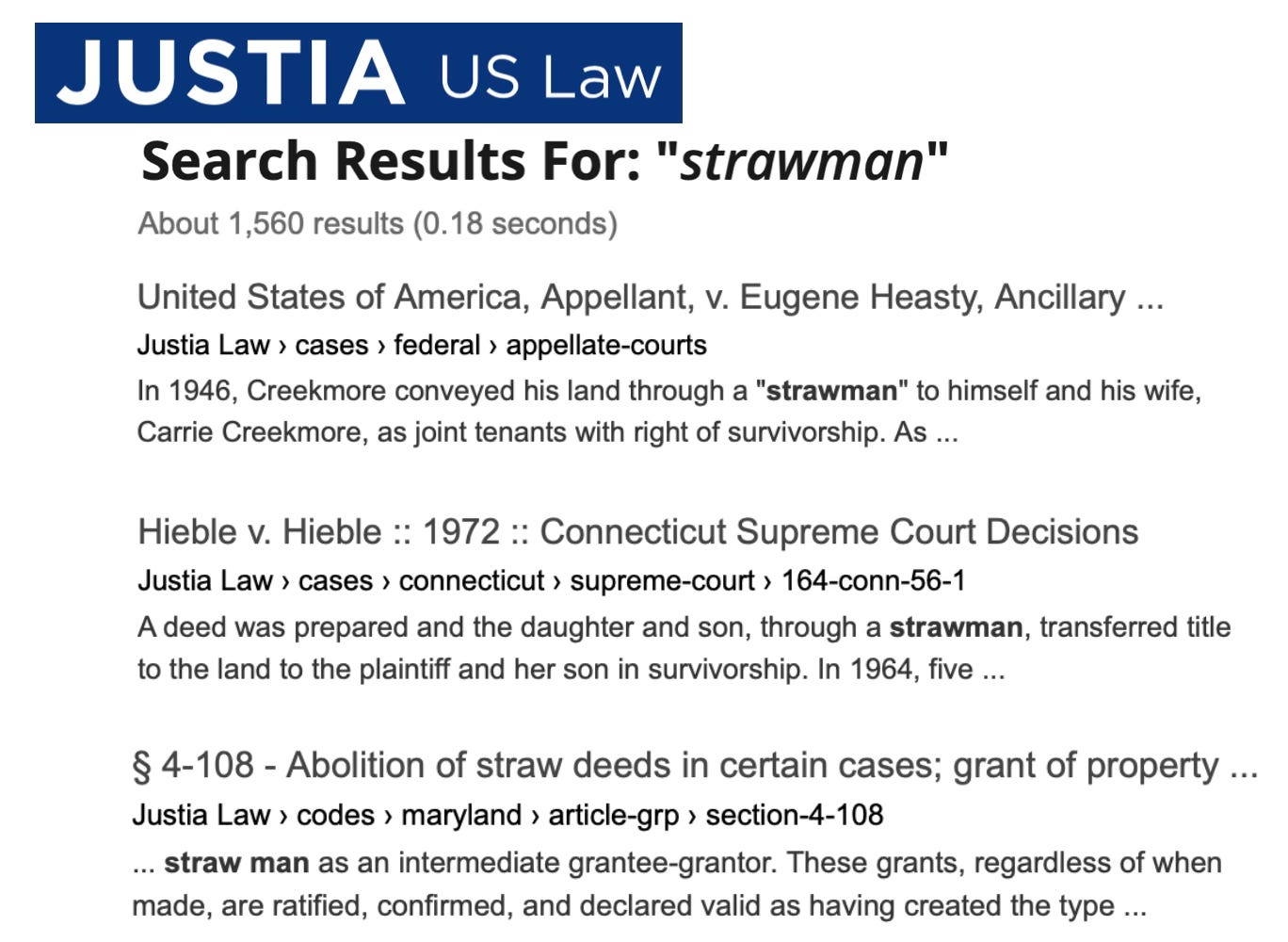

The monstrous customs of the Tartarians and the Scythians recorded in this corporate trade manual may have informed early notions on how to utilize a strawman as a tokenization of the natural human being as a legal stand-in (“in token that there is one buried”). The theory of the legal strawman is attributed to Roger Elvick, a theory that describes a token corporate entity, a legal fiction to which every natural, living human being is legally attached. The strawman theory is mocked by Wikipedia as a “pseudolegal” conspiracy theory, but a quick search of the Justia database brings up 1,500 legal cases addressing the use of the strawman to temporarily hold land in trust.

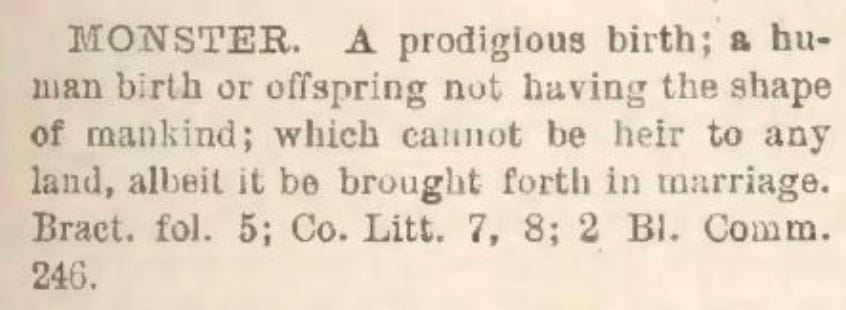

The strawman might also be described as a legal “monster,” a term Black’s Law Dictionary defines as someone “which cannot be heir to any land.” But though a monster can’t permanently inherit, the legal strawman device (as well as women) may act as temporary trustees.

Mary Shelley never names the creature in her story, and since 1818 when the novel was published, readers have conflated Frankenstein with his monster, to the point that the monster is often referred to as “Frankenstein.” And that’s entirely in keeping with the fact that a living natural person’s name is also given to the created strawman, though the second version of the name is in all capital letters.

In John Frampton’s book on Tartaria and Scythia, the author makes an especially intriguing and relevant statement regarding corporate law, writing that the Tartars were “without any lawes or pol:icie.”

The term “policy” originated in Law French, the language that was used by the Normans to express their legal system in England after the invasion of 1066.

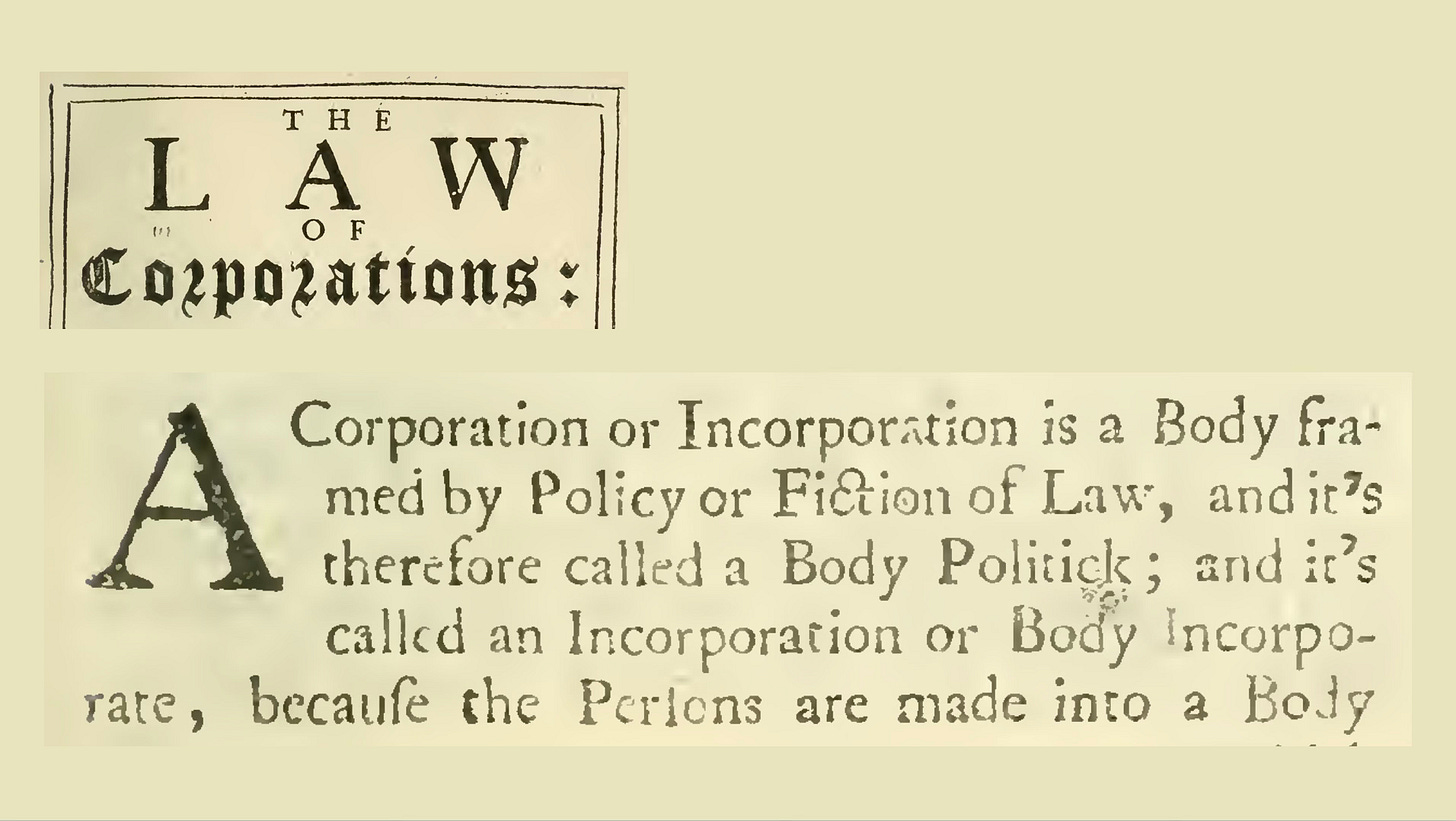

Obviously, “policy” in Frampton’s book refers to something separate from “law,” a distinction we still make today to separate the rule-set used to govern territories like nations (law) and the rule-set used to govern corporations (policy). Sir Edward Coke touched on this distinction in his Commentary upon Littleton of 1628:

‘Bodies politike, &c.’ This is a body to take [land] in succession, framed by policie, and therupon it is called here by Littleton a body politike; and it is also called a corporation, or a body incorporate…

Professor Theodore Lowi also explained the distinction in a 2003 article for the Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, writing that:

‘[P]ublic policy’ is an established concept only in the English language… in the United States, the idea of public policy is relatively recent. Law was the word in the American founding… Public policy did not enter the picture at all until well into the nineteenth century and far from law or legislation.

The term “policy” having such a late entrance into the U.S. lexicon may have been due to the much later incorporation, in 1871, of the governing territory of the District of Columbia. And the Tartars’ lack of “pol:icie” would hold a specific meaning to the members of the Muscovy Company: it would indicate that there were no competing corporations operating in Tartaria.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)