Decoding madwoman chess

How legal fictions were explained in Lewis Carroll's “Through the Looking Glass”

The first thing the Red Queen says to Alice in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass tells us everything we need to know about the story and the hidden messages encoded within. When the Red Queen says all the ways belong to her, she’s referring to her power on the chessboard, as she has the most mobility, being able to move in all eight directions.

[This article is also available as a video.]

But when the game emerged in the 7th century in the area of Persia and India, chess had no queen. Instead of one mate standing next to him, the King had two companions on either side: a vizier, or “advisor,” (the “visor” part of his title, describing his ability to see) and a ferz or counselor. Back then, the vizier moved like a rook and the ferz like a bishop, but each moved only one square at a time. It wasn’t until at least 1000 A.D. that the Queen had replaced them both, and almost 500 years later, still, that the Queen became all-powerful, owning all the ways or directions on the board. We’re told this new role was inspired by Isabella of Spain, also a very powerful and mobile queen and the woman behind what some call Isabella’s Inquisition.

However, a game that would allow its Queen to move unlimited squares in any direction was almost immediately criticized as “madwoman chess,” or more literally, “rabid female chess,” as that level of power was seen as ridiculous. Not even the King had that much power on a chessboard, which is why chess was fun: every piece had to use strategy to overcome its own weakness. Old chess reflected reality, where even the powerful had to strategize and work around their own limitations.

An all-powerful Queen didn’t reflect much strategic reality; her omnidirectional power was based on fiat, simply because the rules now “said so.” Because of Isabella, the Queen had been simply redefined to mean something new, a situation Humpty Dumpty explained to Alice:

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument,’” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

But even though her sweeping redefinition stood, the rabid Queen was never really forgiven for her ill-gotten, sweeping powers. Even today, the chess Queen is considered “mad.” She isn’t portrayed as a noble warrior; she’s still the weird, contrary Queen that Lewis Carroll depicted; in this case, a combination of Elizabeth I’s high forehead with Isabella’s punishing personality.

Mercury-induced madness

In Wonderland, the story before Through the Looking Glass, Alice also falls into a reality that’s been distorted by a change in the rules, and that’s because Lewis Carroll was writing an allegory about the law and its various legal jurisdictions. In Wonderland, Alice found herself in a different jurisdiction: “underland,” an underground jurisdiction. In fact, the book was originally called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. (The topic of children in underground jurisdictions is something I brought up in an earlier video.)

Down the rabbit hole of Wonderland, all the jurisdictional rules and perspectives have changed. It’s here Alice meets the Mad Hatter, who’s mad because of an on-the-job injury: his exposure to mercury vapors used in the making of hats.

But most of the characters in Wonderland seem mad, as if they were all exposed to mercury, and in a way, they were. A bizarre book published in 1641 pre-explained why.

The book was written by John Wilkins, the Bishop of Chester and one of the founders of the Royal Society, believed to be an outgrowth of Sir Francis Bacon’s concept of Solomon’s House that he fleshed out in “New Atlantis.” The Royal Society is still, today, “the oldest continuously existing scientific academy in the world,” according to Wikipedia.

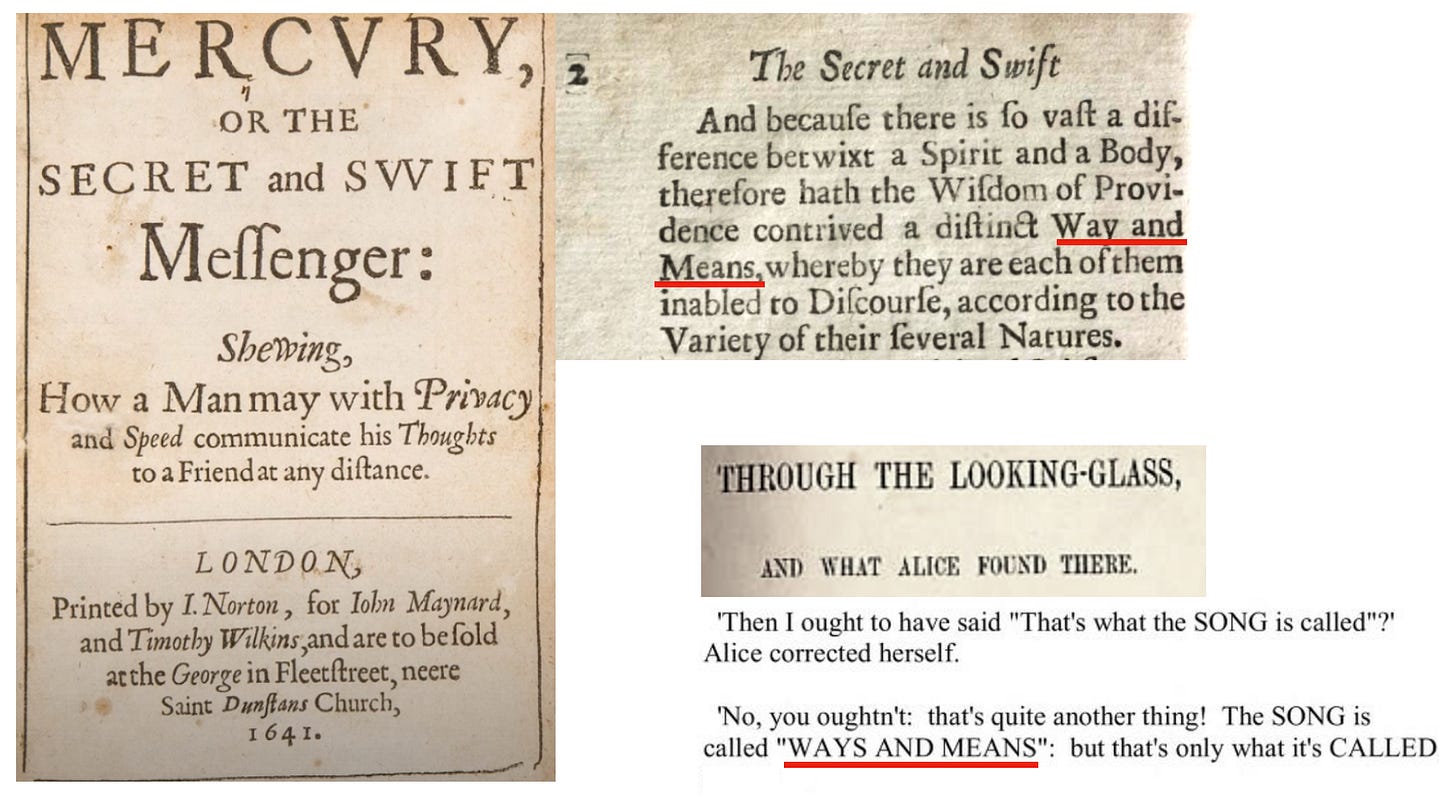

Wilkins published a total of three “mathematical” works: the first discussing his belief there was a habitable world on the moon, and the second concerning the mathematical powers and motions explained by the magic of geometry. But the book that pre-explained why Lewis Carroll’s characters seemed to suffer from mercury-induced madness was Wilkins’ third book, called Mercury, the Secret and Swift Messenger. Or rather, this was its title. What the book was called is a different thing, altogether. The book was initially called the opposite of “spumy froth” by Richard Hatton, Esquire, in one of its introductory pages.

This distinction between what something is called and its title is part of a larger rhetorical concept called the “use-mention distinction” and it’s what gives both Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass their fanciful level of wordplay.

Lewis Carroll messes about with use-mention distinction a lot, but especially at the end of Through the Looking Glass when the White Knight is telling Alice about his song. The song is identified in the following four ways: by the name of the song, what the name of the song is called, what the song is called, and what the song is. These failed attempts at communication all boil down to a distinction between the “song” and its “name,” which are two different things being understood by Alice as the same thing. The name of the song, given as “The Aged Aged Man,” (which could be a reference to the double-A signature of some of the mystery schools) is different than what the song was called, said to be “Ways and Means.” This is an allusion back to the Red Queen’s first words to Alice, mentioned earlier, but it’s also a parliamentary phrase that’s used in Wilkins’ book on page 2. Oddly enough, both the Ways and Means Committee in the House of Commons and the book, Mercury, came into existence in 1641.

But why would the name of a brand new committee on taxation show up in Mercury? Most of the book is pretty straightforward advice, explaining how sending notes on birds conveys them more quickly, or how substitution ciphers work. But on page 2, the term “Way and Means” is used to refer to methods given by God for both the body and spirit to communicate. And an introductory poem mentions how the book can be used by the State:

“Our Legates (the Pope’s messengers) are but men, and often may

Great State-affairs unwillingly betray…

But Secrecy’s now publish’d; You reveal

By Demonstration how we may conceal.”

This is a manual for kings and governments; underlying the book’s surface explanations are basic precepts of propaganda and how to fool people with obscured meaning and obscured grammar. When Alice fails to recognize the White Knight’s use-mention distinction, she provides a useful demonstration of how the masses can be fooled and confused, even to the point of madness, by rhetoric and grammar.

Lewis Carroll gives several clues that he’s been drawing on Wilkins’ book. The messengers of the King, for example, are direct allusions to Mercury, the Secret and Swift Messenger. These messengers are Haigha (a name that rhymes with “mayor”) and Hatta, reincarnations of Wonderland’s March Hare and Mad Hatter, and of course the Hatter was the one most obviously exposed to vapors of mercury.

When the White Queen first mentions Hatta, he’s in prison, presumably for his alarming attitude, something we find out later is an Anglo-Saxon attitude. Hatta’s trial was to start on a Wednesday, the same day of the week that Alice had chosen, back at the beginning of the story, to punish her cat. A connection is being established between Wednesday and punishments for “faults,” of which Alice’s kitten was guilty of three, plus a tacked-on fourth, a sort of quaternary within the ternary: “Her paw went into your eye? Well, that’s your fault, for keeping your eyes open…” This mention of the kitten’s fourth fault seems to imply that, for full dramatic effect, readers should keep their eyes closed and allow the confusing wordplay of the story to take over. Eyes wide shut and all that.

So Wednesday is the day of trial and punishment for faults, but where do the Anglo-Saxons fit in? History tells us that the Anglo-Saxons had changed or glossed the Roman days to reflect their own Anglo-Saxon pagan gods. The name of Wednesday—and what the day was called—was changed to honor Odin (or Woden). Originally, though, Wednesday was the Roman day of Mercury.

This is a story in which rules, definitions, and names are nothing more than decisions, and these decisions can be capriciously changed. Everybody’s doing it — the chess Queen, Humpty Dumpty, the Anglo-Saxons — but if the King finds out, he’s likely to be alarmed and throw you in jail. The capricious changing of names and definitions is a task only for certain people, the people in charge of legal fictions.

Legal titles, like corporations, are legal fictions, just like stories written on flat pieces of paper, but Lewis Carroll, who was very skilled at writing fiction, seems to have wanted to steer clear of flat stories and, even worse, flat arguments, as explained in Mercury: “Plain Arguments and Moral Precepts barely proposed (as in bare, naked, obvious) are more flat in their Operation, not so lively and persuasive, as when they steal into a man’s assent, under the covert of a Parable.” This mention of a “flat” argument should remind us of this riddle from Wonderland: how is a raven like a writing desk? …the answer being that both can produce “notes” that are flat.

Carroll denied that he initially had an answer to that riddle, but if he was trying to avoid a “flat” argument being produced at his writing desk, that may be why he implemented Wilkins’s methods, and especially those concerning the private conveyance of meaning in Chapter 3: by Wilkins’ suggestion of inventing new words (as in Jabberwocky)… or “by a changing of the known Language,” whether Inversion (the looking glass), Diminution (the drink), Augmentation (the food), or Transmutation (the queening of Alice). And it’s the queening of Alice that’s particularly relevant here.

Titles reflect madness

In Through the Looking Glass, Alice begins the game of chess as a pawn, but the Red Queen promises she will be transmuted into a White Queen when she reaches the eighth square. This happens near the end of the story, and once she’s crowned, Alice immediately starts talking to herself—a symptom of madness.

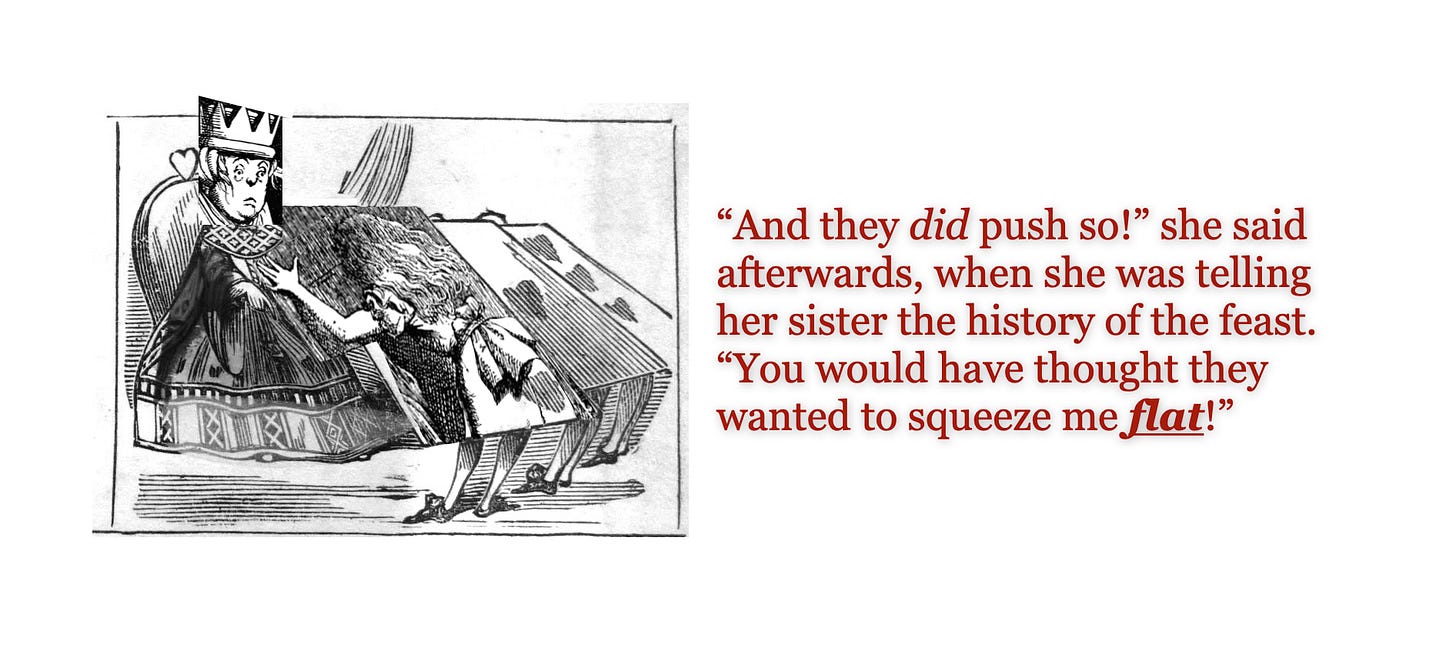

She’s talking to herself because she’s now two people: Alice, a little girl, joined to Alice, a chess Queen. This is how any pawn is promoted in chess; it’s joined through transmutation, a legal incorporation (based on the rules of chess) of the pawn and the Queen. Alice tells us how it’s done: “I wouldn’t mind being a Pawn, if only I might join—though of course I should like to be a Queen, best.”

It’s an incorporation very similar to that done legally on paper involving a real human being joined with a flat, fictional title. Alice even describes the sensation of being flattened after her incorporation: “ ‘And they did push so!’ she said afterwards, when she was telling her sister the history of the feast. ‘You would have thought they wanted to squeeze me flat!’ ” And they did; they were fusing Alice with her flat, legal title—the legal fiction of Queen.

Promotion in chess as a legal fiction of title is just another rule in the rule book, but it goes back at least as far as 1000 A.D., when it was mentioned in a medieval Latin poem about chess, entitled Versus de Scachis:

Candida si sidet fuerit sibi prima tabella,

non color alterius hanc aliquanda capit.

Hoc iter est peditis, si quando pergit in hostem,

ordinis ad finem cumque meare potest.

Nam sic concordant: obliquo tramite, desit

ut si regina, hic quod et illa queat.

It roughly translates to this: “If the [promoted] Queen (written here as fuerit) sits on white in the first file, the color of another can’t be taken. A pawn’s path, advancing against the enemy, reaches the last rank of the board. It is an agreed rule that, moving diagonally, as if a Queen, she [the pawn] may be.”

Here, the title of a promoted Queen is not Queen, (regina), but “feurit,” harkening back to “ferz” and meaning, “as if a Queen.” This is the power, and madness, of a legal fiction. The ancient spelling of “fuerit,” though, doesn’t translate. Revising the spelling to “furit,” we get closer to the original meaning, with translations like rage and furious, bringing us back to the notion of a promoted Queen as an expression of madness.

And yet, one way out of this madness, and one way to sidestep the blurred use/mention distinction, would be to simply give up legal names, or legal titles, and become “undefinable” by those powers that seek to redefine people by fiat. The Gnat suggests this option to Alice, but she fails to see the benefit.

“I suppose you don’t want to lose your name?”

“No, indeed,” Alice said, a little anxiously.

“And yet I don’t know,” the Gnat went on in a careless tone: “only think how convenient it would be if you could manage to go home without it! For instance, if the governess wanted to call you to your lessons, she would call out ‘come here—,’ and there she would have to leave off, because there wouldn’t be any name for her to call, and of course you wouldn’t have to go, you know.”

This idea is pushed further when Alice enters the wood and forgets her name. This allows her to embrace the Fawn and because neither of them can define themselves, they’re able to walk together safely. But once they near the edge of the wood and remember their names, titles, and definitons, the fawn immediately realizes the danger these definitions now pose. This was a nod back to Forest Law that had created a harsh jurisdiction within the King’s forests, in which even the noblemen found themselves temporarily redefined in relation to the deer, the harts, and the fawns.

But there has to be a purpose behind claiming flat legal titles. People don’t just name and define themselves for no reason, and in England, where this fable is set, titles have been used for centuries to provide various ways of access to plots of land. In fact, the plot of this story is a land plot; it’s about legal fictions created and filed in court for the purpose of either owning or using land.

The chessboard in the story is depicted to look like plots of land in the English countryside. And all of Alice’s chess moves take place on well-defined properties with specific owners, tenants, and boundaries.

In order to complete her transmutation into the legal fiction of Queen, Alice must jump over six brooks. It would be naive to think that by “brook,” Lewis Carroll simply meant a stream. A more relevant definition of “brook” involves the “use” of something.

The brooks are the legal “Uses” in Equity Law that Alice hops over and avoids as she makes her way across the chessboard to seek her legal title in Common Law. Presumably, she would rather own the land as a titled Queen than claim “Use” of the land as a pawn.

Francis Bacon explained several centuries ago, in a reading for Gray’s Inn, that a legal “Use” was essentially a Trust, a legal device set up to separate land ownership and the land’s use, usually for agriculture. Once we recognize this, we can start to see that the chessboard in Through the Looking Glass is a legal framework illustrating obligations of land “Use” out in the country or county, so named for the accounting of farm obligations, or taxes.

[Continue reading Decoding madwoman chess, part 2…]

Exchequer

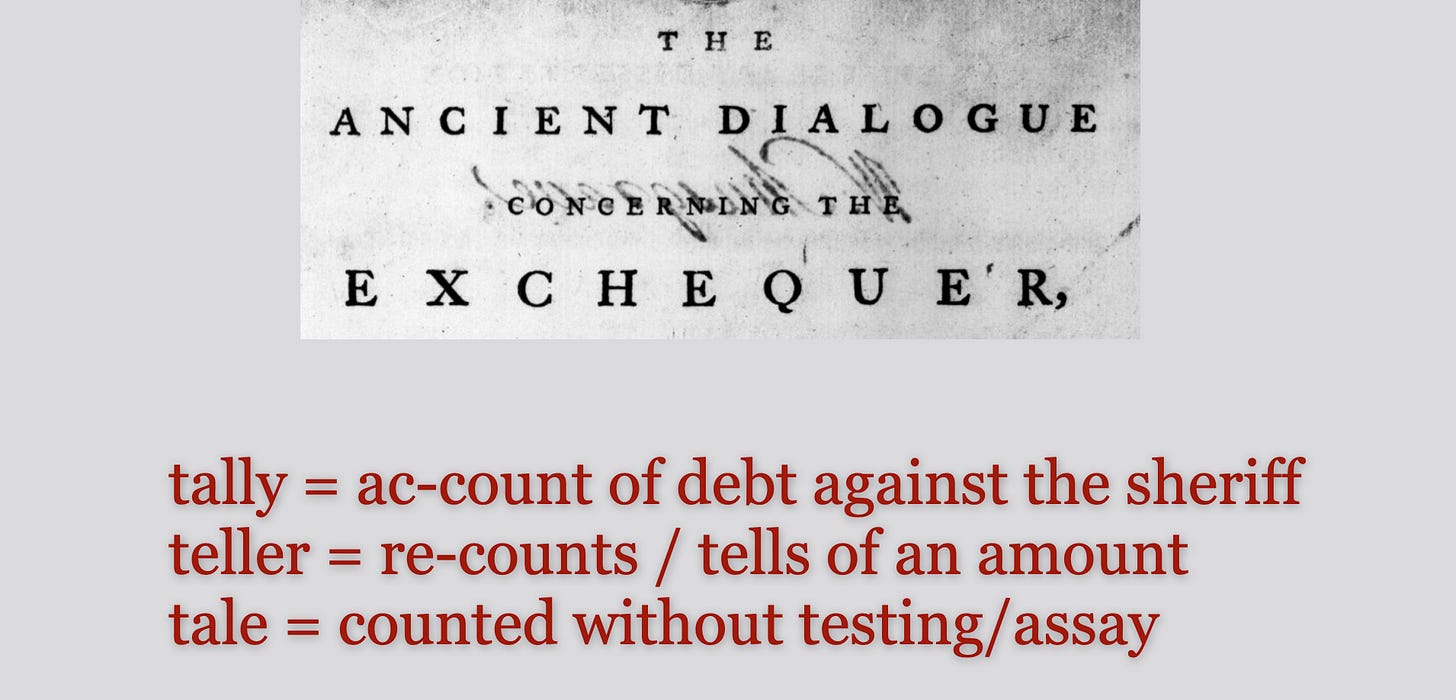

The game of chess was called the “game of state” in the introduction to Versus de Scachis, and we can see the connection clearly in the two medieval words defining them: scacchi, Italian for chess, and scaccarii, Latin for treasurer, or what the English called the Exchequer. The Ancient Dialogue Concerning the Exchequer, written around 1180 A.D. tells us that the treasury office was called the office of Exchequer because it was set up “like a chessboard.” That’s because a checkered cloth was laid out on its counting table. Tax payments were piled onto the cloth’s grid of squares and columns to be counted by the “calculator,” and various positions of rank had assigned seating around the checkered table for observing these calculations.

Black’s Law Dictionary described the set-up this way: “A chequered cloth resembling a chess-board which covered the table in the exchequer, and on which, when certain of the king’s accounts were made up, the sums were marked and scored with counters. Hence the Court of Exchequer, or Curia Scaccarii, derived its name.”

The Exchequer was the office where property tax was turned in to the crown, but not by those on the property. Property taxes had to be collected from the outlying farms by the sheriff, who then brought them into the Exchequer, himself. The tax debt of his shire actually fell on the sheriff, himself; he was liable for the debt.

The farms were laid out in rough squares in the English shires, the counties, so named because the product of their toil would be semiannually counted. Land in these counties was divided into hides, similar to a family farm. A hundred farms or hides were grouped together as “hundreds,” and several “hundreds” would comprise a shire. Because the sheriff was responsible for the tax debt, he would move about on this rural chessboard, collecting taxes and depositing them on the chessboard of the Exchequer.

The medieval sheriff was most famously depicted as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood, and his connection to the office and the doings of the Exchequer is signified in this movie on his shield and his belt: the checkerboard. The same was true for the Treasurers, who used heraldic “fesse chequy” on their coat of arms to indicate their connection to the Exchequer office and its role in the collection of revenue. We still see this on police uniforms today. In England, it’s the modern result of utilizing Scottish heraldry on the insignia, and is still an indication of the police role in revenue collection, historically counted on a checkered, chessboard cloth.

But the Ancient Dialogue Concerning the Exchequer describes an opposition between the Exchequer and the Sheriff: “[A]s in chess the battle is fought between kings, so in this it is chiefly between two that the conflict takes place and the war is waged, the treasurer, namely, and the sheriff who sits there to render account; the others sitting by as judges, to see and to judge.” It brings to mind the situation between the Lion and the Unicorn in Through the Looking Glass — two officers working for the king but fighting one anotehr — and it likely reflects the pressure on a Sheriff, the Shire Reeve, to enforce unpopular laws and collect taxes seen as unfair, while both the King and his Exchequer are safely insulated from all the unhappy subjects. In fact, the people of Nottingham blamed the Sheriff for the high rate of tax, but how much of his despotic behavior was wrapped up in the fact that he was personally liable for their debt, a debt for which his own possessions could be confiscated?

Checkmate

The whole feudal system seems to have been based on capricious rules both reflecting and creating madness, and this madness wasn’t limited to the Queen of the chessboard.

In fact, it was madness that defined the end of the chess game. In 1525, the term “checkmate” was explained in another medieval poem, printed as an introduction to Vida’s Scacchi Ludus: “We say he’s mated, then the game is done. (As if we thought him mad, or yet unwise, for in th’Italian, Mate, that sense implies.)”

And maybe the game of chess was only ever meant to be a tall tale, fantastic, fun, and full of fibs. But even with this term, “tall tale,” we’re driven back to the chessboard of the Exchequer, who employed the “tellers” of such tales.

The terms tally, teller, and tale all refer to the act of counting. A teller was the position in charge of counting the money coming into the Exchequer, and today, a “teller” of tales is someone re-counting information.

The payment of taxes by “tale” meant money coming in that was trusted enough not be tested by assay, melting the coins down to check the fineness of the gold or silver. A tall tale was a large amount of money stretching along the column or file of the Exchequer table, though the term has come to mean something unbelievable, fictional, or even deceptive.

And perhaps these fictional titles of Queen and King, Winner, and even Land Owner, are nothing more than tall tales. Scacchi Ludus pointed out centuries ago, that the King, “even he who, from above, his Title draws, is, in this point, a slave to his own laws.” Titles don’t change reality. To have ever thought they did was a form of madness.

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)