Cupid's Tartarian Arrow

On the Fifth Day of The Chymical Wedding, Christian Rosenkreutz is led by his page to explore the King’s Treasury in the dungeon of the castle. There he sees what I call the “sepulcher of symbolism,” Lady Venus, and her son, Cupid.

In the margin of the text it reads, “Thalamus Veneris Sepultae,” which translates to “the burial chamber of Venus.”

But if we parse out these Latin words we find that “Thalamus Veneris” means “come to the room,” which is precisely what Christian has done, and it’s as if he’s been summoned to do so. Here, The Chymical Wedding is speaking to mental alchemy, the process of elevating energy through the tree-trunk of the chakras in the torso, through meditation, to enter a specific place or room of the mind. We use the term thalamus to describe a part of the brain located in the center, between the two dualistic hemispheres. And in Latin, thalamus means “room.” So the personal alchemical symbolism here is that Christian is moving his energy to his thalamus.

Normally, we think of moving energy up the chakras to the pineal gland, and that gland is involved in this process, but it’s important to realize that the thalamus “room” is also a part of this process.

Because the pineal gland is cone-shaped, it’s usually symbolized by the pinecone, and we’ve seen depictions of the pine tree in the work of Bacon and Shakespeare, including the cloven pine of The Tempest. The tree here in the castle’s sepulcher is said to be “unknown,” but it’s possible that it could be some type of pine or conifer. And although it’s said to be dropping its fruit into the copper kettle, the internet tells us that a pinecone is considered a “fruit,” a woody fruit that contains seeds.

Fire opens a pinecone to release its seeds, especially in serotinous pines, where according to Google, “the cones are sealed with resin that only melts when exposed to high heat from a fire.” This trait is called “serotiny,” and it’s interesting that the root of “sero” shows up in the word serotonin.

In The Chymical Wedding, fire has a role with regard to the tree in this scene of the story: “…on every corner there burned a small Taper of Pyrites, of which I had before taken no notice; for the fire was so clear, that it looked much liker a Stone than a Taper. From this heat the Tree was forced continually to melt, yet it still produced new Fruit.” Pyrite, of which these tapers were made, is a mineral composed of iron and sulfur. The root “pyr” means fire and describes a feature of pyrite: it produces a spark when struck by metal.

Melatonin, produced by the pineal gland, also has the effect of lowering the body’s core temperature, and it’s interesting that we’re presented with the lowering and raising of temperature. Google tells us that “Serotonin and melatonin are both involved in sleep and that serotonin is a precursor to melatonin.” The root sero, in Latin, means late (as the seeds of seritonous pines are held for years until a fire releases them). And the root mela is widely understood to mean “black,” but that’s from Greek etymology; in Latin, the root mela meant apple. In Latin, might the hormones of serotonin and melatonin be symbolically pointing to “late apples”? Are the symbolic pinecones dropping, as fruit, these “late apples”?

In his essay on Cupid, the Atom, Francis Bacon saw the infant god as the representation of seeds: “He is described with great elegance as a little child, and a child for ever; for things compounded are larger and are affected by age; whereas the primary seeds of things, or atoms, are minute and remain in perpetual infancy. Most truly also is he represented as naked: for all compounds are masked and clothed; and there is nothing properly naked, except the primary particles of things.”

Next, Christian is led from this “thalamus” room through a trap door and down some stairs, a path that seems to be patterned after the positioning of the pineal gland in relation to the thalamus. “Herewith I espied a rich Bed ready made, hung about with curious Curtains, one of which he drew, where I saw the Lady Venus stark naked (for he heaved up the Coverlets too) lying there in such Beauty, and a fashion so surprising, that I was almost besides myself… So she was again covered, and the Curtain drawn before her, yet she was still in my Eye…” He pinpoints her location in his own head, and it’s not within his two eyes used for vision; it’s his single eye, the pineal gland’s mystical designation in eastern religions as the third eye.

The two drapes covering Venus—the curtains and the coverlets—seem to correspond to the dura- and pia mater, the outermost and innermost layers, respecitvely, of the membrane protecting the brain. Dura mater means, in Latin, hard mother, while pia mater, the name of the inner layer, means pious mother… as if being closer to the inner sanctum of this temple of the brain makes this one more pious. And, of course, the very concept of matter is derived from the term for mother.

Venus is mother to Cupid, and like her son, she’s associated with love and attraction. In Bacon’s essay on Cupid, he writes that these two are working toward the same purpose, to compound or bond, which is what a chymical wedding also achieves: “For Venus excites the general appetite of conjunction and procreation; Cupid, her son, applies the appetite to an individual object. From Venus therefore comes the general disposition, from Cupid the more exact sympathy.”

But in addition to piercing couples with his arrow to attract them to one another, Cupid has another purpose: to increase temperature, and it’s because of Cupid that these pyrite tapers are burning.

But this is where the allegory shifts from spiritual or mental alchemy to the manipulation of metals.

metallurgical pyromaniac

In Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 153,” a maid of the goddess Diana douses Cupid’s “love-kindling fire” with cold water, and Cupid re-ignites his fire in the single eye of the author’s mistress:

Which borrowed from this holy fire of Love,

A dateless lively heat still to endure…

Cupid is in the business of kindling burning love, and his “lively heat” is also mentioned in the 1691 semi opera, King Arthur: 'Tis I… that have warm'd ye. In spite of cold weather I've brought ye together…”

But Cupid doesn’t just use fire to incorporate human hearts; he also uses it to incorporate metals. We get a glimpse of this in The Chymical Wedding when he uses fire to warm his arrow: “Yet can I not (said Cupid) let it pass unrevenged, that you were so near stumbling upon my dear Mother; with that he put the point of his Dart into one of the little Tapers, and heating it a little, pricked me with it on the hand…” Then, Cupid marries—or incorporates—man with metal, though this isn’t a real incorporation, but rather a symbolic punishment for Christian.

Because Cupid’s source of warmth is fire, two plays from the 1600s compare a weak or failing Cupid to a scarecrow, a symbol easily threatened by fire. One play to do this is Cupid’s Revenge where the god Cupid is being erased from the culture of Lycia as a “vain and fruitless superstition,” and Cupid’s statues and temples are being removed: “Priest do not stare, I must deface your Temple, though unwilling, And your god Cupid here must make a Scarcrow…” Another play to make this comparison is Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, where Benvolio says, “We’ll have no Cupid hoodwink'd with a scarf, Bearing a Tartar's painted bow of lath Scaring the ladies like a crow-keeper.”

In both of these examples, Cupid is failing at his job: he’s accused of being a lazy god in one and scaring rather than luring the ladies in the other. But combining this symbol of a scarecrow with Benvolio’s mention of a Tartar’s painted bow reveals that this line is a reference to Tartaria and the information John Frampton presented in his 1580 book, A Discovery of the Countries of Tartaria, Scithia, and Cataya.

Frampton’s book details an odd burial ritual involving filling with hay the skin of the deceased person, or the skin of a dead horse, essentially creating what we’d call a “scarecrow” today. I’ve speculated in another video that this ritual likely spawned the concept of the corporate strawman because, among the Tartars, the hay-filled body served as a token for one buried. This is exactly how the legal, corporate strawman functions: as a token for another, conjoining two legal entities into one. So the incorporating Cupid, when failing at his job to incorporate man and woman, shifts into incorporating the strawman or scarecrow with the living man.

Like Cupid, the wild, barbarous Tartars—who used straw men as incorporated tokens— also understood metallurgy. They’d been gathering information about it from the Chinese since the 10th century, and as such, the Tartars were reported to have adorned their costumes with gold, and forged metal arrows and knives. But this passage from Frampton’s book reveals something interesting: “…they [the Tartars] take it for a heinous matter to cast a knife into the fire, or touch the fire therewith, or take the meat out of the pot with a knife.”

Why would they be anxious to keep their knives out of the fire? Probably because their knives weren’t tempered. As Google tells us, “an untempered knife will likely melt in a fire… without tempering, the steel is much softer and more susceptible to melting when exposed to high heat.” The act of tempering involves heating the metal to a specific temperature below its melting point, and then allowed to cool slowly, a slightly different process than incorporating metals into alloys, which involves melting the base metal followed by rapid cooling. Slow cooling is known as annealing and is used to soften metals and make them more malleable, whereas rapid cooling is used to harden metals.

What the Tartars were anxious to protect their knives from, then, was the act of cupellation: a metallurgical process that separates metals in ores and alloys by heating them to high temperatures. Cupellation is the act of melting at high heat to separate, rather than melting and cooling to incorporate. Cupellation is the alchemical dissolution that undoes the chymical wedding.

The two words, Cupid and cupellation, seem like they might be related. In fact, this is where I first suspected that Cupid was a little god of metallurgy—a god of alloy incorporation—and that his function was simply later applied to the human act of incorporation, of wedding.

The etymology of cupellation claims to go back to the Latin word “cuppa,” meaning the cupel or vessel in which the metal assays were performed. But I think it’s doubtful that cupel and cupellation derive from cuppa, for two reasons. First, because there’s another Latin word with much more relevance to the act of high-heat separation in alchemy: cupio, meaning “to smoke, boil, or move violently.”

My second reason is that the word cupio is much older than the word cuppa, a term from Late Latin, between the 3rd to 6th centuries A.D. There’s archeological evidence of cupellation relics from the Bronze Age, “suggesting its use as early as the 4th millenium B.C.” And that corresponds to the age of the word “cupio,” which comes from a Proto-Indo-European root, a linguistic system dating from 4500 B.C. Cupio, then, could easily have been the term actually used during cupellation in the Bronze Age to mean a violent boil that would produce the heat necessary for melting.

Once again, etymological resources have either been lying to us, or have been lazy in their research.

But the word cupio evolved in Classical Latin to also mean “to desire or long for,” very much in keeping with the state Cupid is known to generate. The fact that cupio evolved to mean “I want” and Cupid means “greedy” also suggests that these two words, and by extension, cupellation, are likely related terms.

In fact, Cupid’s role is usually to bring an unwilling partner into a romantic coupling. If a man rejects a woman, just shoot him with Cupid’s arrow, and then he’ll join with her.

In the world of metallurgy, gold is that unwilling partner, as St. Germain writes in Discourse 7 of The I Am Discourses: “Gold does not long for nor adhere to anything else. All other metals or alloys cling to it. Gold is this way because it is of a pure element.”

Since gold is an unwilling partner, it requires the flaming arrow of Cupid to be coaxed into the bonding involved in a gold alloy or a gold telluride like calaverite or sylvanite. Tellurides are naturally occurring, but in metallurgy, the purpose of creating a gold alloy is to harden what is otherwise a soft metal.

This brings up something interesting: while gold is incorporated with other metals to harden it, a tartrate is used to soften metals and make them more malleable.

Tartrate is also known as Tartar.

Does that make it Tartarian?

Black Tartarian Cherry

Tartar salt forms naturally in wine casks and on wine bottle corks when potassium binds with tartaric acid. And tartrates are especially likely to form if the wine is cooled below 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

There’s a wine on the market today made from Black Tartarian cherries, and these cherries have been cultivated since at least the early 1700s in Circassia, Russia. On this Mercator map from 1595, the land bounded with pink is designated as all one place with the name Tartaria here in the center. This pink boundary reaches right up to the eastern shore of the Black Sea, where Circassia was located, in the area we currently call Georgia.

Frampton’s 1580 book tells us that 200 years earlier, in the late 1300s, “…about this time they [meaning the Tartars] overcame and brought into subjection to them the Georgians…” Further down on page 12, it states that, “When these Georgians would enter into battle, they accustomed to drink a bottle of wine that they use to carry with them…” Was this wine made from Tartarian Cherries? It seems likely. We know that cherry wine will produce tartrate crystals, just as grape wines do, so might the tartrate crystals that are a natural byproduct of wine have been named from this form of Tartarian wine? It’s certainly possible.

And although tartaric acid wasn’t discovered until 1769, the ancient Greeks were aware of tartar in a partially purified form. According to Panzarasa in his 2015 paper, Rediscovering Pyrotartaric Acid, “The formation of tartar during vinification has been known since ancient times: it was initially called faex vini [meaning wine sediment], and the word tartarus began to appear in the alchemical literature of the eleventh century.”

Much later, alchemists of the 15, 16, and 1700s were fascinated by “tartarus” and Blaise De Vigenère wrote in the 1500s that tartar was “one of the subjects which those who experiment with fire greatly abuse.” And Johannes de Monte-Snyder in the 1600s: “By means of Tartar the metals are changed into living Mercury, and this happens because while quantitatively the salt is increased, the Earth begins to predominate until the bond is broken.” We could take out all the details in the middle and just say, “By means of Tartar… the bond is broken.”

This is alchemy, dissolution, breaking the bonds of the chymical wedding.

In 1655, Jean van Helmont specifically noted the usefulness of tartarus in the act of dissolution in Ortus Medicinae: “If you cannot attain this arcanum of fire [i.e., the alkahest], learn then to make salt of tartar volatile and complete your dissolutions by means of it.” He also mentioned that tartarus from wine was used to make ink, which showed that it wasn’t the wine, but the dregs or sediments of the wine that produced the color. Today, tartaric acid is still used in the gold and silver plating, the cleaning of metals, and making the blue ink for blue-prints.

But why were the alchemists experimenting with fire abusing tartar? Because tartar salt, when can lower the melting point of metals. Fluxum nigrum is made from the partial calcination (heating at high temperature with restricted oxygen) of tartar for the purpose of creating a melting agent, a flux to lower the melting point.

melting a tree

Now let’s decode the strange symbols Christian Rosenkreutz sees inside the sepulcher.

“This Sepulcher was triangular, and had in the middle of it a Kettle of polished Copper, the rest was of pure Gold and precious Stones; in the Kettle stood an Angel, who held in his Arms an unknown Tree, from which it continually dropped into the Kettle; and as oft as the Fruit fell into the Kettle, it turned into Water too, and ran out from thence into three small Golden Kettles standing by…”

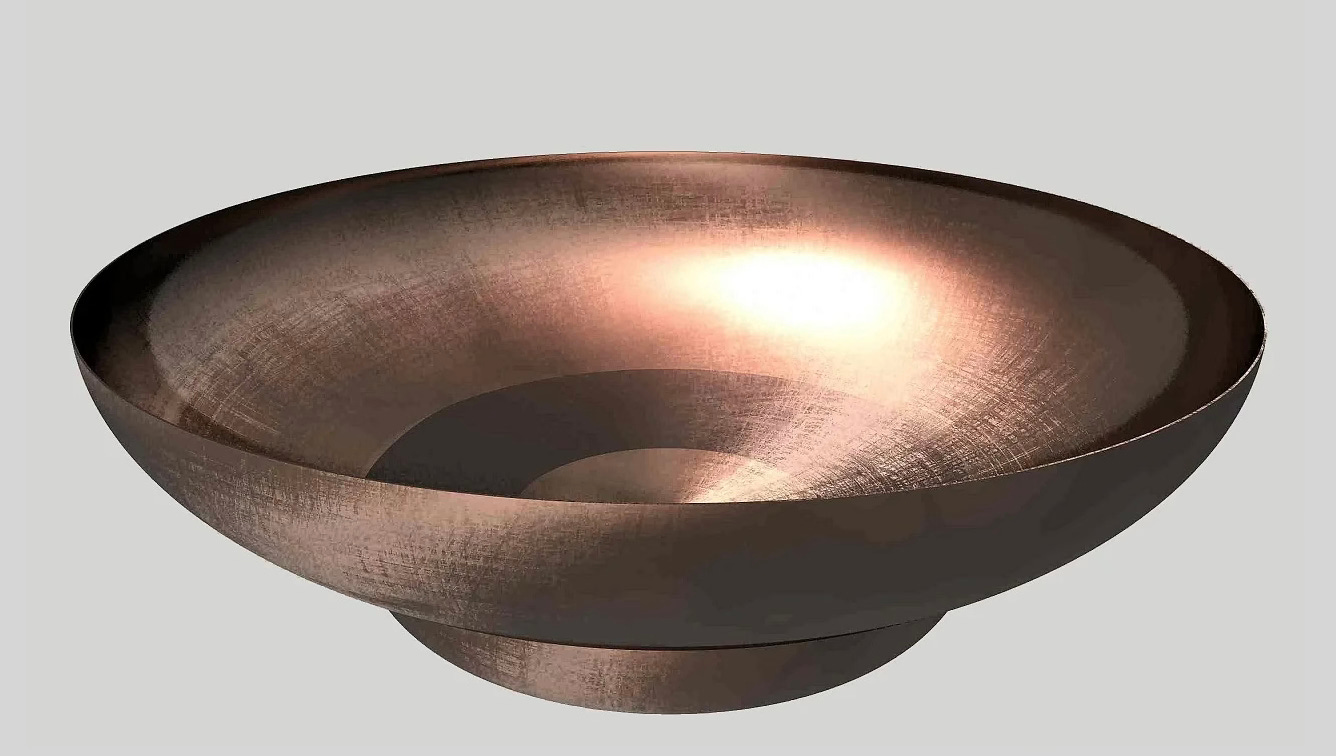

The kettle is made of copper because copper is the metal associated with Venus. Not only that, but its symbol on the table of elements is CU from its Latin name cuprum: another name that seems connected to Cupid, cupel, and cupellation.

In the early 1600s, a kettle wasn’t necessarily a container with a spout for boiling water; it was also a large vessel for cooking food and, although this is kettle is most definitely fictional and symbolic, this concave kettle is the only type in which an angel could stand and be visible.

Placing the angel in the kettle is somewhat like having the angel stand in a pit, and recall that Tartarus, in addition to being a deity and a wine sediment, is also a concave pit, known as the underworld of ancient Greece.

According to the Theoi Greek Mythology website, the combination of the sky’s arch and the underworld’s bowl frame reality, itself: “Tartaros was envisaged as the opposite of the sky, an inverted-dome lying beneath the flat earth. Together the Ouranion-dome [Ouranos being the primordial god of the sky] and Tartarean-pit enclosed the entire cosmos in an egg-shaped or spherical shell.” The arch and pit are each half of the whole. Stacked, they form the egg-shaped sphere.

What this all suggests is that the kettle is copper tartarus or copper tartrate. Copper is used in alloys to improve the malleable of metals, a function of tartrate, but copper tartrate, specifically, is used in electroplating metals, attracting and binding gold or silver to the surface of another metal—a very cupid-like project.

Electroplating wasn’t possible in 1616 when The Chymical Wedding was published, but other forms of plating base metals with gold and silver had been performed since at least medieval times, and Palafox writes of silver plated prizes given to Tartarian soldiers well before modern electroplating was developed.

The angel standing in the cupric tartrate kettle would likely be Haniel, the archangel associated with Venus. This angel is also associated with a ray of turquoise light, in keeping with copper’s turquoise patina and the blue-green color of cupric tartrate, and is described sometimes as male, sometimes female. Variants of the name Haniel include Anael or Aniel, which are homophones of the word “anneal,” meaning to heat a metal and allow it to cool slowly in order to make it more malleable… just like many tartrate compounds.

In the arms of the angel is a tree forced to continually melt as it drops fruit. Cupid is in the process of attempting to completely melt the tree with his tapers. So why would he do this? Wood doesn’t melt, but that’s because its melting point is higher than its combustion point; it’ll burn before it melts. So what Cupid needs here is a melting agent to lower wood’s melting point, again pointing to the function of tartar salt compounds like fluxum nigrum.

Next in the story, the page explains to Christian the need for the tree to melt: “Now behold (said the page) what I heard revealed to the King by Atlas, When the Tree (said he) shall be quite melted down, Then shall Lady Venus awake, and be the Mother of a King…” We might assume that this means that Cupid, as the child of Venus, will be elevated to the status of a king. But in the process of plating one metal with another, “the king” refers to gold as the most desirable metal that can be USED in that process. The “mother” in the plating process refers to the second generation metal plate acting like a mold. So Cupid, here, seems to be facilitating a metallurgical process of molding gold plate in the image of Venus using the melting agent of tartarus.

And I wonder if this function of tartar salt, and its natural production in tartarian cherries, might have something to do with the scrubbing of Tartaria from modern historical records and maps. There may be something really powerful and useful in tartarus (tartar salt), especially in the earth’s grid system and its natural production of energy. I don’t claim to know what that is, but it’s another area of research that might prove beneficial.

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)

![Stephanie McPeak Petersen [] writer in resonance](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!jz_a!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63c3ebac-43b9-478a-9aed-12c7f5458a70_600x600.jpeg)